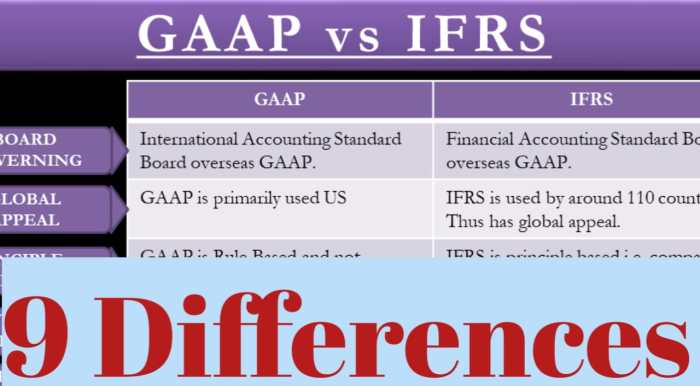

GAAP vs IFRS What’s the Difference? This question is central to understanding the complexities of international financial reporting. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), primarily used in the United States, and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), adopted globally by many countries, offer distinct approaches to accounting practices. Understanding their core differences is crucial for investors, analysts, and anyone navigating the global financial landscape.

This exploration will delve into the key discrepancies between GAAP and IFRS, examining their historical development, contrasting their methodologies for revenue recognition, inventory valuation, and intangible asset treatment, and analyzing the impact on financial statement presentation and key financial ratios. We will also explore the implications for lease accounting and the ultimate effects on investor and creditor decision-making. By clarifying these differences, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the nuances between these two dominant accounting frameworks.

Introduction

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are the two major sets of accounting rules used globally to standardize how companies report their financial information. They provide a framework for creating financial statements that are consistent, comparable, and reliable, allowing investors, creditors, and other stakeholders to make informed decisions. While both aim for transparency, they differ significantly in their approach and application.

The primary purpose of both GAAP and IFRS is to ensure the accuracy and consistency of financial reporting. This promotes investor confidence and facilitates efficient capital allocation within the global marketplace. However, their historical development and the bodies governing them have led to distinct characteristics and interpretations.

Origins and Governing Bodies of GAAP and IFRS

GAAP, primarily used in the United States, evolved organically over decades, shaped by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). The SEC’s influence stems from its mandate to protect investors, and the FASB, a private-sector organization, develops and issues GAAP standards. In contrast, IFRS, developed by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), is a principles-based system adopted by over 140 countries. The IASB is an independent, international organization that aims for global consistency in financial reporting. This difference in origin – a rules-based system (GAAP) versus a principles-based system (IFRS) – is a key factor influencing their differences.

Key Differences in the Development of GAAP and IFRS

The development of GAAP and IFRS has followed distinct paths. GAAP’s evolution was largely reactive, addressing specific accounting issues as they arose, often leading to a detailed, rules-based system. This resulted in a large volume of specific rules and guidelines, making it potentially more complex to interpret and apply. IFRS, on the other hand, adopted a more proactive approach, focusing on establishing general principles and allowing for more professional judgment in their application. This principles-based approach aims for greater flexibility and adaptability to different business contexts, but it can also lead to greater diversity in interpretation across jurisdictions. The convergence efforts between GAAP and IFRS aim to reduce these differences, but significant variations still exist.

Key Differences in Revenue Recognition

Revenue recognition, a cornerstone of financial reporting, differs significantly between Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). These differences can impact a company’s reported financial performance and its overall valuation. Understanding these discrepancies is crucial for investors, analysts, and anyone interpreting financial statements prepared under either framework.

Comparison of GAAP and IFRS Revenue Recognition Principles

GAAP, primarily used in the United States, historically employed a more rules-based approach to revenue recognition, often leading to a variety of acceptable methods depending on the specific industry and transaction. This resulted in inconsistencies in how similar transactions were reported across different companies. IFRS, on the other hand, adopts a more principles-based approach, emphasizing the substance of transactions over their legal form. The adoption of IFRS 15, Revenue from Contracts with Customers, brought a significant degree of harmonization, establishing a five-step model for revenue recognition that applies globally under IFRS. While GAAP has converged significantly towards a similar model (ASC 606), subtle differences remain.

The Five-Step Model Under IFRS 15 and its GAAP Equivalent

IFRS 15’s five-step model provides a structured approach to revenue recognition:

- Identify the contract(s) with a customer. This involves determining if a legally enforceable agreement exists that specifies the rights and obligations of both parties.

- Identify the performance obligations in the contract. A performance obligation is a promise to transfer a distinct good or service to the customer. Distinctness is determined by whether the customer can benefit from the good or service independently, or if it is highly integrated with another promised good or service.

- Determine the transaction price. This is the amount of consideration a company expects to receive in exchange for transferring promised goods or services. Consideration may include variable amounts, such as discounts, rebates, or incentives, which must be estimated at the contract inception.

- Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract. If the contract includes multiple performance obligations, the transaction price must be allocated to each obligation based on their relative standalone selling prices.

- Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation. Revenue is recognized when the customer obtains control of the good or service. This often occurs upon transfer of the good or service, but it could occur earlier or later depending on the specific circumstances.

ASC 606, the GAAP equivalent, mirrors this five-step model closely. However, minor differences exist in areas like the determination of distinctness and the treatment of certain specific transactions. The core principle of recognizing revenue when control is transferred remains consistent across both standards.

Impact of Different Revenue Recognition Methods on Financial Statements, GAAP vs IFRS What’s the Difference?

Different revenue recognition methods can significantly impact a company’s reported revenue, expenses, and ultimately, its profitability. For example, a company using a percentage-of-completion method under GAAP for a long-term construction project will recognize revenue gradually over the project’s lifetime. In contrast, a company using the completed-contract method would only recognize revenue upon project completion. This difference in timing affects reported revenue, gross profit, and net income during the project’s duration. Similarly, variations in the application of the five-step model under IFRS 15 or ASC 606 can lead to different revenue recognition patterns, impacting key financial statement metrics like revenue growth, profitability margins, and cash flow. The impact can be particularly pronounced for companies with significant long-term contracts or complex transactions.

Differences in Inventory Valuation

Inventory valuation is a crucial aspect of financial reporting, significantly impacting a company’s reported cost of goods sold, gross profit, and ultimately, net income. Both GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) allow for several methods to value inventory, but they differ in their permitted choices and the implications of those choices. Understanding these differences is vital for comparing the financial statements of companies using different accounting standards.

Acceptable Inventory Valuation Methods

GAAP and IFRS both permit the use of cost formulas to determine the value of inventory. However, the specific methods allowed and their application differ slightly. Under GAAP, companies can choose from the First-In, First-Out (FIFO), Last-In, First-Out (LIFO), and weighted-average cost methods. IFRS permits FIFO and the weighted-average cost method, but explicitly prohibits LIFO. This difference stems from IFRS’s focus on fair presentation and the belief that LIFO can distort the matching of revenues and expenses.

Implications of FIFO, LIFO, and Weighted-Average Cost

The choice of inventory valuation method directly impacts a company’s reported financial results, particularly during periods of fluctuating prices. FIFO assumes that the oldest inventory is sold first, resulting in a cost of goods sold that reflects older costs. This leaves the ending inventory valued at more recent costs. Conversely, LIFO (permitted only under GAAP) assumes that the newest inventory is sold first, resulting in a cost of goods sold that reflects more recent costs and ending inventory valued at older costs. The weighted-average cost method calculates a weighted-average cost per unit based on the total cost of goods available for sale divided by the total number of units available.

During periods of inflation, LIFO will generally result in a higher cost of goods sold and a lower net income compared to FIFO. This is because the higher recent costs are matched against revenues. Conversely, during periods of deflation, LIFO will result in a lower cost of goods sold and a higher net income. FIFO generally produces a smoother result across inflationary and deflationary periods. The weighted-average cost method provides a balance between the extremes of FIFO and LIFO, resulting in a cost of goods sold that reflects a blend of older and newer costs.

Situations Where Inventory Valuation Method Significantly Impacts Financial Reporting

The choice of inventory valuation method can significantly impact financial reporting in several situations. For example, during periods of rapid inflation or deflation, the differences between FIFO, LIFO, and weighted-average cost can be substantial. This can affect key financial ratios like gross profit margin, inventory turnover, and profitability. Furthermore, the choice of method can influence tax liabilities, as the cost of goods sold impacts taxable income. Consider a company experiencing rapid inflation: Using LIFO would result in a higher cost of goods sold, leading to lower taxable income and potentially lower tax payments. However, this same method would lead to a lower reported net income, which could negatively affect investor perception.

A company operating in a volatile market with fluctuating prices might find its reported profits significantly impacted by the chosen inventory valuation method. For example, a construction company experiencing fluctuating material costs would see vastly different reported profits depending on whether it uses FIFO or weighted-average costing. Similarly, a grocery store chain with perishable goods would likely find the weighted-average method more suitable than FIFO, as it would better reflect the average cost of the goods sold, considering the continuous flow of inventory. The selection of an appropriate method must carefully consider the specific industry, business environment, and the need for consistency over time.

Treatment of Intangible Assets

Intangible assets, unlike tangible assets, lack physical substance. Their value is derived from rights, privileges, or competitive advantages. Accounting for these assets differs significantly under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), primarily concerning amortization, impairment, and the treatment of research and development (R&D) costs.

Both GAAP and IFRS require intangible assets to be recognized on the balance sheet if certain criteria are met, such as being identifiable, controlled by the entity, and expected to generate future economic benefits. However, the subsequent accounting treatment, particularly amortization and impairment testing, varies.

Expand your understanding about Cash Flow Statement Explained with the sources we offer.

Amortization and Impairment of Intangible Assets

Under GAAP, intangible assets with finite useful lives are amortized systematically over their useful lives. Impairment is tested when there is an indication that the asset’s carrying amount may not be recoverable. If impairment is indicated, the asset is written down to its fair value less costs to sell. IFRS also requires amortization for intangible assets with finite useful lives, but the impairment testing is more frequent and comprehensive. IFRS mandates annual impairment reviews for all intangible assets, regardless of whether there are indications of impairment. The impairment loss is calculated as the difference between the carrying amount and the recoverable amount (higher of fair value less costs of disposal and value in use).

Research and Development Costs

A key difference lies in the treatment of research and development (R&D) costs. Under GAAP, research costs are expensed as incurred, while development costs are capitalized only if specific criteria are met (e.g., technical feasibility is established, intent to complete and use or sell the asset is demonstrated, ability to use or sell the asset is demonstrated, and future economic benefits are probable). IFRS, on the other hand, requires all research costs to be expensed as incurred. Development costs are capitalized only if certain criteria are met, similar to GAAP, but the criteria are slightly different. This difference often leads to variations in reported earnings and asset values between companies using GAAP and IFRS.

Examples of Intangible Assets and Their Accounting

Consider a software company developing a new application. Under GAAP, the research phase costs would be expensed, while the development phase costs might be capitalized if the criteria are met. Under IFRS, the research phase costs are expensed, and development costs may be capitalized if the IFRS criteria are met. Another example is a patent acquired by a pharmaceutical company. Both GAAP and IFRS would require the patent to be amortized over its useful life and tested for impairment. However, the specifics of the amortization method and impairment testing may differ. A trademark, on the other hand, may be considered to have an indefinite useful life, meaning it is not amortized but tested for impairment annually under both standards.

Comparison of Intangible Asset Treatment

| Intangible Asset Type | GAAP Amortization | IFRS Amortization | Impairment Testing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patent | Amortized over useful life | Amortized over useful life | Annual under IFRS; when indicators exist under GAAP |

| Trademark | Not amortized (indefinite life) | Not amortized (indefinite life) | Annual under IFRS; when indicators exist under GAAP |

| Copyright | Amortized over useful life | Amortized over useful life | Annual under IFRS; when indicators exist under GAAP |

| Goodwill | Not amortized; tested for impairment | Not amortized; tested for impairment | Annual under IFRS; when indicators exist under GAAP |

Depreciation Methods

Depreciation, the systematic allocation of an asset’s cost over its useful life, is handled differently under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). While both frameworks aim to reflect the decline in an asset’s value accurately, the permissible methods and their application vary, leading to potential differences in reported financial statements. Understanding these differences is crucial for comparing companies reporting under different standards.

Both GAAP and IFRS allow for several depreciation methods, but the specific choices and their application might differ. The selection of an appropriate method depends on factors such as the asset’s nature, its expected usage pattern, and the company’s specific circumstances. The impact of the chosen method is significant, affecting the reported net income, asset values on the balance sheet, and ultimately, the company’s overall financial position.

Allowable Depreciation Methods under GAAP and IFRS

GAAP and IFRS generally permit the straight-line, declining balance, and units-of-production methods. However, the application and specific requirements might vary. For example, while both allow for the declining balance method, the maximum rate allowed might differ depending on the specific asset and company policies. Under GAAP, the choice of method should be consistent with the asset’s expected pattern of consumption of economic benefits. IFRS emphasizes the need for the depreciation method to reflect the asset’s consumption pattern and should be reviewed at the end of each financial year.

Impact of Depreciation Methods on Financial Statements

The choice of depreciation method directly influences a company’s reported net income and balance sheet values. The straight-line method results in a constant depreciation expense each year, leading to a smoother income pattern. In contrast, the declining balance method results in higher depreciation expense in the early years and lower expense in later years, potentially affecting profitability reporting in the short-term. This impacts the net income reported, affecting key financial ratios like profitability and return on assets. The accumulated depreciation, which is a contra-asset account, also impacts the net book value of assets reported on the balance sheet. A higher depreciation expense will lead to a lower net book value.

For example, consider a machine purchased for $100,000 with a useful life of 10 years and no salvage value. Under the straight-line method, annual depreciation would be $10,000. Under the double-declining balance method (an accelerated method), the first year’s depreciation would be $20,000 (20% of $100,000), significantly higher than the straight-line method. This difference would continue throughout the asset’s life, with the double-declining balance method resulting in higher depreciation expense in the early years and lower expense in the later years.

Factors Influencing the Selection of a Depreciation Method

The selection of a depreciation method is not arbitrary. Several factors influence this choice. The most important factors include the asset’s expected pattern of use, the asset’s useful life, and the company’s accounting policies. For example, assets that are expected to decline rapidly in value, such as technology equipment, might be better depreciated using an accelerated method like the declining balance method. Conversely, assets with a more consistent pattern of use, such as buildings, might be better suited to the straight-line method. Furthermore, companies must ensure consistency in their depreciation methods over time unless there is a significant change in the asset’s usage or economic conditions. Management’s judgment and the specific industry practices also play a role in the selection process. It’s vital that the chosen method aligns with the asset’s economic reality and is applied consistently to provide a fair and accurate representation of the company’s financial performance.

Financial Statement Presentation: GAAP Vs IFRS What’s The Difference?

GAAP and IFRS, while both aiming to provide a fair presentation of a company’s financial position, differ in their prescribed formats and structures for financial statements. These differences impact how assets, liabilities, and equity are presented, as well as the required disclosures. Understanding these nuances is crucial for anyone analyzing financial statements prepared under either standard.

The fundamental difference lies in the emphasis placed on certain aspects of financial reporting. GAAP tends to be more rules-based, while IFRS leans towards a principles-based approach. This results in variations in the presentation of information, although the overall goal of transparency remains consistent.

Format and Structure of Financial Statements

GAAP typically requires a balance sheet, an income statement, a statement of cash flows, and a statement of changes in equity. IFRS similarly mandates these statements, but allows for some flexibility in presentation order and format. For example, while both standards require a statement of cash flows, the specific classifications and presentation of cash flow items might differ slightly. The balance sheet under GAAP often presents assets in order of liquidity, while IFRS allows for more flexibility in the order of presentation, potentially prioritizing assets based on importance or relevance to the business.

Presentation of Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

While both GAAP and IFRS require the presentation of assets, liabilities, and equity, the specific classifications and order may vary. For example, the classification of certain items as current or non-current assets or liabilities might differ based on the specific criteria used under each standard. The presentation of equity might also differ, with GAAP emphasizing a more detailed breakdown of retained earnings compared to IFRS. Furthermore, IFRS allows for more flexibility in the presentation of comprehensive income, which includes items such as unrealized gains and losses on certain investments. This contrasts with GAAP’s more prescribed approach.

Required Disclosures

Both GAAP and IFRS require extensive disclosures to ensure transparency and comparability. However, the specific disclosures required differ. For instance, GAAP might require more detailed disclosures related to specific industry practices or regulatory requirements, while IFRS may emphasize disclosures related to significant accounting policies and judgments. A key difference lies in the level of detail required in explaining the accounting policies used. IFRS places a greater emphasis on the narrative explanation of accounting policies, providing more context and justification for the choices made. This enhances the transparency of the financial reporting process. For example, a company using IFRS might provide more detailed explanations regarding the methods used for impairment testing of intangible assets than a company reporting under GAAP.

Impact on Financial Ratios

The differences between Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) can significantly influence the calculation and interpretation of key financial ratios. These variations stem from the differing treatments of revenue recognition, inventory valuation, intangible assets, and depreciation methods, among other areas. Consequently, comparing companies using different accounting standards requires careful consideration of these potential discrepancies. Understanding these impacts is crucial for accurate financial analysis and informed decision-making.

The impact on financial ratios is not uniform across all ratios. Some ratios are more susceptible to changes in accounting standards than others. For instance, ratios heavily reliant on the income statement, such as profit margins, will be directly affected by variations in revenue recognition and expense reporting. Similarly, balance sheet-based ratios, like the debt-to-equity ratio, will reflect differences in asset valuation. A thorough analysis requires a careful examination of the specific accounting policies employed and their effect on the relevant line items.

Examples of Impacted Ratios

Several key financial ratios are notably influenced by the choice between GAAP and IFRS. The differences can lead to varying interpretations of a company’s financial health and performance. For example, a company reporting under IFRS might show a higher net income due to different revenue recognition rules, leading to a higher return on equity (ROE) compared to a similar company using GAAP. Conversely, differences in depreciation methods could impact the return on assets (ROA) calculation.

Comparative Table of Key Financial Ratios

| Ratio | GAAP | IFRS | Potential Differences and Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Return on Equity (ROE) | Net Income / Average Shareholder Equity | Net Income / Average Shareholder Equity | Differences in net income due to variations in revenue recognition (e.g., long-term contracts) and expense capitalization can significantly impact ROE. A company using IFRS might report higher net income and therefore a higher ROE if it recognizes revenue earlier than under GAAP. |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | Net Income / Average Total Assets | Net Income / Average Total Assets | Differences in depreciation methods and intangible asset amortization can lead to variations in net income and total assets, thus affecting ROA. Accelerated depreciation under IFRS could lead to lower reported net income and potentially lower ROA. |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Debt / Total Equity | Total Debt / Total Equity | Differences in asset valuation (e.g., intangible assets) can influence the total equity figure, impacting the debt-to-equity ratio. More conservative valuation under GAAP might result in a lower equity figure and thus a higher debt-to-equity ratio compared to IFRS. |

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | While less directly impacted, differences in inventory valuation (e.g., FIFO vs. LIFO) can subtly influence current assets and therefore the current ratio. Using FIFO under IFRS could result in a higher current ratio compared to using LIFO under GAAP in periods of rising prices. |

Consolidation of Financial Statements

Consolidating financial statements of a parent company and its subsidiaries presents distinct approaches under GAAP and IFRS. These differences stem from varying interpretations of control and the subsequent treatment of minority interests. Understanding these variations is crucial for accurate financial reporting and cross-border comparisons.

The core difference lies in the definition of control. Both GAAP and IFRS generally require consolidation when a parent company holds a majority ownership stake (typically over 50%), but IFRS takes a broader perspective, considering factors beyond simple ownership percentages to determine control. This can lead to situations where IFRS requires consolidation even when ownership is less than 50%, if the parent company holds significant influence.

Control and Consolidation

GAAP primarily focuses on the ownership percentage to determine control. If a parent company owns more than 50% of a subsidiary’s voting stock, consolidation is typically required. However, IFRS uses a more nuanced approach. It considers power over the investee, exposure to variable returns from its involvement with the investee, and the ability to use its power to affect its returns. This “control model” allows for consolidation even if the parent company holds less than 50% of the voting shares, provided it has the power to govern the financial and operating policies of the subsidiary. For instance, if a parent company holds 40% ownership but possesses key management positions and voting rights through contractual agreements, IFRS might necessitate consolidation.

Accounting for Minority Interests

Under GAAP, minority interests are typically presented as a separate line item within equity on the consolidated balance sheet. This reflects the portion of the subsidiary’s net assets not attributable to the parent company. IFRS presents minority interests similarly, showing the non-controlling interest’s share of the net assets of the subsidiary. However, there might be subtle differences in the presentation format and terminology used. Both standards require the disclosure of the minority interest’s share of profit or loss in the consolidated income statement.

Impact of Consolidation Methods

Different consolidation methods, while not explicitly defined as separate methods under either GAAP or IFRS, lead to variations in the parent company’s reported financial figures. For example, the treatment of intercompany transactions (transactions between the parent and subsidiary) affects consolidated revenue, expenses, and assets. Eliminating these intercompany transactions is crucial to avoid double-counting and presenting a true picture of the consolidated entity’s performance. Furthermore, the valuation methods used for assets and liabilities of subsidiaries before consolidation can impact the final consolidated figures. Differences in accounting policies between the parent and subsidiary can also create discrepancies in the consolidated financial statements. For example, if the subsidiary uses a different depreciation method than the parent, the consolidated depreciation expense might differ from what would be reported if both used the same method. This necessitates adjustments during the consolidation process to ensure consistency.

Lease Accounting

Both GAAP (ASC 842) and IFRS 16 significantly changed how leases are accounted for, moving away from the previous distinction between operating and finance leases. This shift aims for greater transparency and comparability in financial reporting by requiring most leases to be recognized on the balance sheet.

Both standards require lessees to recognize a right-of-use asset and a lease liability on their balance sheets for most leases. The key differences lie in the specifics of how these items are measured and presented, leading to variations in the reported financial position and performance.

Lease Classification

Under both GAAP and IFRS 16, a lessee evaluates each lease to determine whether it meets the criteria for a finance lease or an operating lease. While the underlying principles are similar, subtle differences in the specific criteria can lead to different classifications. For instance, the presence of a bargain purchase option might be treated differently under each standard’s specific guidance, resulting in a lease being classified as a finance lease under one standard and an operating lease under the other. The classification significantly impacts the subsequent accounting treatment.

Right-of-Use Asset and Lease Liability Measurement

Both GAAP and IFRS 16 require the lessee to recognize a right-of-use (ROU) asset and a lease liability. However, the measurement of these items can differ slightly. For example, the initial measurement of the ROU asset and lease liability might involve different approaches to incorporating lease incentives or initial direct costs. Subsequent measurement also involves nuances in how lease payments and other related costs are incorporated into the carrying amount of the assets and liabilities. These differences, although often minor, can lead to discrepancies in the reported amounts on the balance sheet.

Impact on the Balance Sheet and Income Statement

The adoption of ASC 842 and IFRS 16 has led to significantly larger balance sheets for many companies, primarily due to the recognition of lease liabilities. This increased leverage might impact credit ratings and other financial metrics. The income statement impact is more nuanced. While the overall effect on net income might not be dramatic in many cases, the presentation of lease expenses is altered. Instead of a single operating lease expense, companies now report depreciation expense on the ROU asset and interest expense on the lease liability, providing a more detailed picture of the cost of leasing.

Illustrative Scenario

Imagine Company X leases a building for 10 years. Under GAAP, certain lease terms might lead to the lease being classified as an operating lease, while under IFRS 16, the same lease could be classified as a finance lease due to the specific criteria each standard uses. As a result, under GAAP (assuming an operating lease classification), the lease payments would be expensed over the lease term, with no asset or liability recognized on the balance sheet. However, under IFRS 16 (assuming a finance lease classification), Company X would recognize a ROU asset and a lease liability on its balance sheet, reflecting the present value of future lease payments. The ROU asset would be depreciated over the lease term, and the lease liability would be amortized, resulting in depreciation and interest expense on the income statement. This scenario highlights the potential for significant differences in reported financial information under the two standards.

Impact on Investors and Creditors

The choice between GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) and IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) significantly impacts how companies report their financial performance and position. This, in turn, directly affects the investment decisions of investors and the creditworthiness assessments of creditors. Understanding these differences is crucial for making informed financial decisions.

The variations between GAAP and IFRS in areas like revenue recognition, inventory valuation, and intangible asset treatment lead to differences in reported financial figures. These discrepancies can influence key financial ratios, potentially altering a company’s perceived profitability, liquidity, and solvency. Consequently, investors may interpret a company’s financial health differently depending on the accounting standards used, leading to varying investment strategies. Creditors, similarly, will adjust their credit risk assessments based on these reporting differences.

Impact on Investment Decisions

Differences in reported earnings and assets under GAAP and IFRS can directly influence investment decisions. For instance, a company reporting higher earnings under IFRS might appear more attractive to investors compared to the same company reporting under GAAP if the GAAP figures are lower due to more conservative accounting practices. This could lead investors to value the company more highly under IFRS, potentially affecting stock prices and investment allocations. Conversely, a company appearing riskier under IFRS due to higher reported debt levels (perhaps stemming from different lease accounting treatments) might deter investors seeking lower-risk investments. The choice of accounting standards therefore becomes a key factor in comparative financial analysis for investors.

Impact on Credit Risk Assessments

Creditors rely heavily on financial statements to assess a borrower’s creditworthiness. Discrepancies between GAAP and IFRS reports can significantly influence these assessments. For example, a company’s debt-to-equity ratio, a crucial creditworthiness indicator, could differ substantially under GAAP and IFRS due to variations in how assets and liabilities are reported. A higher debt-to-equity ratio under one standard compared to the other could lead to different credit ratings and interest rates offered by lenders. Creditors may demand higher interest rates or stricter loan covenants if they perceive higher risk under a particular accounting standard, even if the underlying economic reality remains the same. This highlights the importance of understanding the implications of accounting standards when evaluating a company’s creditworthiness.

Examples of Impact on Investment and Credit Decisions

Consider a hypothetical scenario involving two companies, Company A and Company B, both in the same industry. Company A reports its financials under GAAP, while Company B uses IFRS. If Company B reports significantly higher earnings than Company A due to differences in revenue recognition, investors might perceive Company B as more profitable and potentially invest more heavily in it. However, if a closer examination reveals that these differences are primarily due to more aggressive accounting practices under IFRS, this perception could be misleading. Similarly, if Company A reports a lower debt-to-equity ratio than Company B under their respective standards, creditors might offer Company A more favorable loan terms, even if the underlying financial strength is comparable. These examples underscore the need for investors and creditors to understand the nuances of GAAP and IFRS to make informed decisions.

Wrap-Up

In conclusion, the choice between GAAP and IFRS significantly impacts financial reporting, influencing the presentation of financial statements and the interpretation of key financial ratios. While both aim for transparency and comparability, their distinct approaches necessitate a careful understanding of their nuances. Investors, creditors, and financial analysts must be aware of these differences to accurately assess financial health and make informed decisions in the global marketplace. The ongoing evolution of both standards underscores the importance of staying informed about the latest updates and interpretations.

Questions Often Asked

What is the primary difference in how GAAP and IFRS handle lease accounting?

Under IFRS 16, most leases are recognized on the balance sheet, while GAAP (ASC 842) provides more options, allowing for some leases to be treated off-balance sheet. This impacts leverage ratios and overall financial position.

Which standard is more principles-based, and which is more rules-based?

IFRS is generally considered more principles-based, offering more flexibility in application, while GAAP is often described as more rules-based, providing more specific guidance.

Are there any efforts to converge GAAP and IFRS?

Yes, there have been ongoing efforts towards convergence, but significant differences remain. Complete harmonization is unlikely in the near future.