Double Entry Accounting Explained with Examples sets the stage for understanding this fundamental accounting method. This comprehensive guide unravels the intricacies of double-entry bookkeeping, tracing its historical development and highlighting its advantages over simpler single-entry systems. We’ll explore the core accounting equation, debits and credits, and the practical application of these principles through numerous real-world examples, making this complex topic accessible to all.

From basic transactions to more advanced concepts like adjusting entries and accrual accounting, this guide provides a step-by-step approach to mastering double-entry bookkeeping. We’ll use clear explanations, illustrative examples, and visual aids to ensure a thorough understanding of this essential accounting skill.

Introduction to Double-Entry Accounting: Double Entry Accounting Explained With Examples

Double-entry bookkeeping is a fundamental accounting method that ensures the accuracy and reliability of financial records. It’s based on a simple yet powerful principle: every financial transaction affects at least two accounts. This ensures that the accounting equation – Assets = Liabilities + Equity – always remains balanced. This seemingly small detail revolutionized financial record-keeping and remains the cornerstone of modern accounting.

The fundamental principle of double-entry bookkeeping is that for every debit entry, there must be a corresponding credit entry of equal value. This ensures that the total debits always equal the total credits, maintaining the balance of the accounting equation. This seemingly simple concept is the key to preventing errors and providing a comprehensive view of a business’s financial health.

A Brief History of Double-Entry Bookkeeping

While the exact origins are debated, the widespread adoption of double-entry bookkeeping is generally credited to Italian merchants in the 15th century. Luca Pacioli, a Franciscan friar and mathematician, is often considered the “father” of double-entry bookkeeping for his detailed description of the system in his 1494 treatise, *Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni et proportionalita*. Before this, single-entry systems were common, leading to frequent errors and inconsistencies in financial records. Over centuries, the system evolved, adapting to the increasing complexity of business transactions and the rise of new technologies, but its core principles have remained remarkably consistent.

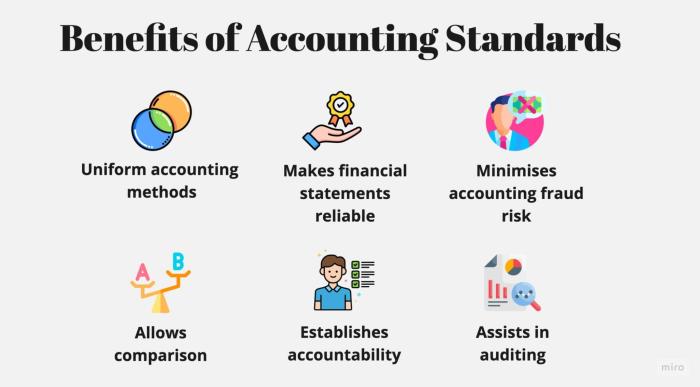

Advantages of Double-Entry Bookkeeping over Single-Entry

Double-entry bookkeeping offers several crucial advantages over its simpler predecessor, single-entry bookkeeping. Single-entry only records one side of a transaction, making it prone to errors and offering limited insight into a business’s financial position. In contrast, double-entry provides a comprehensive and auditable record of all transactions, facilitating more accurate financial reporting and better decision-making.

- Improved Accuracy: The requirement of two entries for every transaction minimizes the risk of errors and omissions.

- Enhanced Financial Reporting: Double-entry provides a complete picture of a company’s financial health, allowing for the generation of accurate financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, cash flow statement).

- Better Fraud Detection: The inherent checks and balances within the system make it more difficult to conceal fraudulent activities.

- Increased Trust and Credibility: The rigorous nature of double-entry increases the credibility and trustworthiness of financial records for stakeholders such as investors, lenders, and regulators.

Analogy for Understanding Double-Entry Bookkeeping

Imagine a scale perfectly balanced. This scale represents the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity). Every transaction is like adding or removing weights from either side of the scale. A debit is like adding weight to one side, while a credit is like adding weight to the other. To maintain balance, the weight added to one side must always be matched by an equal weight added to the other side. This ensures the equation remains balanced, mirroring how double-entry bookkeeping ensures the accounting equation always holds true. For example, if a company buys equipment with cash (an asset), the cash account decreases (credit) and the equipment account increases (debit) by the same amount. The scale remains balanced.

The Accounting Equation

The fundamental principle underlying double-entry bookkeeping is the accounting equation. This equation ensures that the balance sheet always remains balanced, reflecting the financial position of a business at any given point in time. Understanding this equation is crucial for grasping the core concepts of accounting.

The accounting equation demonstrates the relationship between a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity. It states that the total value of a company’s assets must always equal the sum of its liabilities and equity. This balance is maintained with every transaction recorded. Any change on one side of the equation necessitates a corresponding change on the other side, ensuring the equation remains in equilibrium.

Components of the Accounting Equation, Double Entry Accounting Explained with Examples

The accounting equation,

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

, consists of three key components:

- Assets: These are resources controlled by a company as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity. Examples include cash, accounts receivable (money owed to the company), inventory, equipment, and buildings.

- Liabilities: These are present obligations of an entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits. Examples include accounts payable (money owed by the company), loans payable, and salaries payable.

- Equity: This represents the residual interest in the assets of the entity after deducting all its liabilities. It’s essentially the owners’ stake in the business. Equity increases with owner contributions (investments) and profits, and decreases with owner withdrawals and losses.

Transaction Effects on the Accounting Equation

Every financial transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining the balance of the accounting equation. Let’s illustrate this with some examples:

- Example 1: Owner invests cash into the business. This increases both assets (cash) and equity (owner’s capital). The equation remains balanced.

- Example 2: Purchase of equipment on credit. This increases assets (equipment) and liabilities (accounts payable). Again, the equation remains balanced.

- Example 3: Revenue earned from services provided. This increases assets (cash or accounts receivable) and equity (retained earnings). The equation remains balanced.

- Example 4: Payment of expenses. This decreases assets (cash) and decreases equity (retained earnings). The equation remains balanced.

Examples of Asset, Liability, and Equity Accounts

The following table provides further examples of different accounts categorized under assets, liabilities, and equity:

| Assets | Liabilities | Equity |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | Accounts Payable | Owner’s Capital |

| Accounts Receivable | Salaries Payable | Retained Earnings |

| Inventory | Loans Payable | Dividends |

| Prepaid Expenses | Taxes Payable | Revenue |

| Equipment | Unearned Revenue | Expenses |

Types of Accounts and Their Impact

Understanding the different types of accounts is crucial for accurate double-entry bookkeeping. Each account type has a specific purpose and a normal balance, either debit or credit, which indicates the side where increases are recorded. The impact of debit and credit entries varies depending on the account type.

Double-entry bookkeeping relies on the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. All transactions affect at least two accounts to maintain this balance. This system provides a comprehensive view of a business’s financial position and performance.

Account Types and Normal Balances

The major account types are assets, liabilities, equity, revenue, and expenses. Each has a normal balance that determines whether a debit or credit increases the account balance. Remembering these normal balances is essential for correctly recording transactions.

| Account Type | Description | Normal Balance | Debit Increases/Decreases | Credit Increases/Decreases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Resources owned by the business (cash, accounts receivable, equipment) | Debit | Increases | Decreases |

| Liabilities | Obligations owed by the business (accounts payable, loans payable) | Credit | Decreases | Increases |

| Equity | Owner’s investment in the business (capital, retained earnings) | Credit | Decreases | Increases |

| Revenue | Income generated from business operations (sales revenue, service revenue) | Credit | Decreases | Increases |

| Expenses | Costs incurred in generating revenue (rent expense, salaries expense) | Debit | Increases | Decreases |

The Impact of Debit and Credit Entries

Debits and credits always have opposite effects on accounts within the same category. For example, a debit increases assets and expenses, while a credit decreases them. Conversely, a credit increases liabilities, equity, and revenue, while a debit decreases them. This dual effect ensures the accounting equation remains balanced after every transaction.

Consider a scenario where a company receives $1,000 cash from a customer for services rendered. This transaction increases cash (an asset – debit) and increases service revenue (revenue – credit). Both accounts are impacted, keeping the accounting equation in balance.

Another example: The company pays $500 for rent. This transaction increases rent expense (expense – debit) and decreases cash (asset – credit). Again, the accounting equation remains balanced.

The fundamental principle is that every transaction affects at least two accounts, one with a debit and one with a credit, maintaining the balance of the accounting equation.

Recording Transactions with Examples

Now that we understand the fundamental principles of double-entry bookkeeping, including the accounting equation and the various types of accounts, let’s delve into the practical application of recording business transactions. This involves systematically documenting each transaction to maintain accurate financial records. Each transaction will affect at least two accounts, adhering to the fundamental principle of double-entry bookkeeping.

The process of recording transactions begins with a journal entry. A journal entry is a chronological record of business transactions. It shows the accounts affected, the amounts involved, and whether the accounts are debited or credited. Debits always equal credits, maintaining the balance of the accounting equation.

Journal Entries for Various Transactions

The following examples illustrate how various transactions are recorded using journal entries. Each example clearly shows the accounts affected, the debit and credit amounts, and the date of the transaction. Note that the date is crucial for tracking the chronological order of events.

- Transaction: Received $5,000 cash from a customer for services rendered.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 26, 2024

Account Debit Credit Cash $5,000 Service Revenue $5,000 Explanation: Cash increases (debit), and service revenue increases (credit).

- Transaction: Purchased $2,000 of inventory on credit from a supplier.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 27, 2024

Account Debit Credit Inventory $2,000 Accounts Payable $2,000 Explanation: Inventory increases (debit), and accounts payable increases (credit).

- Transaction: Paid $1,000 rent expense in cash.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 28, 2024

For descriptions on additional topics like Cost Accounting vs Financial Accounting: Key Differences, please visit the available Cost Accounting vs Financial Accounting: Key Differences.

Account Debit Credit Rent Expense $1,000 Cash $1,000 Explanation: Rent expense increases (debit), and cash decreases (credit).

- Transaction: Sold goods for $3,000 on credit. The cost of goods sold was $1,500.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 29, 2024

Account Debit Credit Accounts Receivable $3,000 Sales Revenue $3,000 Explanation: Accounts receivable increases (debit), and sales revenue increases (credit).

Journal Entry for Cost of Goods Sold:

Date: October 29, 2024

Account Debit Credit Cost of Goods Sold $1,500 Inventory $1,500 Explanation: Cost of Goods Sold increases (debit), and Inventory decreases (credit).

Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries are made at the end of an accounting period to ensure that revenues and expenses are recognized in the correct period. These entries update accounts to reflect the accurate financial position of the business.

- Transaction: Accrued salaries of $500 at the end of the month.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 31, 2024

Account Debit Credit Salaries Expense $500 Salaries Payable $500 Explanation: Salaries expense is increased (debit), and salaries payable is increased (credit) to reflect the unpaid salaries.

- Transaction: Prepaid insurance of $1,000 was purchased at the beginning of the year. $250 has been used during the year.

Journal Entry:

Date: October 31, 2024

Account Debit Credit Insurance Expense $250 Prepaid Insurance $250 Explanation: Insurance expense is increased (debit), and prepaid insurance is decreased (credit) to reflect the insurance used during the period.

The Trial Balance and its Significance

The trial balance is a crucial report in accounting, serving as a snapshot of the general ledger’s data at a specific point in time. It summarizes all the debit and credit balances from the accounts, verifying the fundamental accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) remains balanced. This process is vital for detecting errors before preparing financial statements.

A trial balance is prepared by listing all accounts from the general ledger with their respective debit or credit balances. The total of all debit balances is then compared to the total of all credit balances. If these totals are equal, it indicates that the double-entry bookkeeping system is functioning correctly and the accounting equation is in balance. This doesn’t guarantee the complete absence of errors, but it significantly increases confidence in the accuracy of the financial records.

Trial Balance Preparation

Preparing a trial balance involves systematically extracting account balances from the general ledger. The general ledger is a collection of individual accounts that record all financial transactions. Each account shows a running balance, which is the difference between the total debits and the total credits posted to that account. To prepare the trial balance, each account’s balance is transferred to a worksheet. The worksheet typically includes columns for account names, debit balances, and credit balances. The debit and credit columns are then totalled separately. A trial balance is considered accurate if the total debits equal the total credits.

Importance of a Balanced Trial Balance

A balanced trial balance provides reasonable assurance that the accounting equation remains intact and that no major errors have occurred in the recording of transactions. It’s a fundamental step in the accounting cycle, forming the basis for preparing the financial statements. A balanced trial balance allows accountants to proceed with confidence to the next stage of the accounting process, preparing financial statements such as the income statement and balance sheet.

Dealing with an Unbalanced Trial Balance

An unbalanced trial balance indicates a mathematical error somewhere in the recording or summarizing of transactions. This discrepancy requires careful investigation. Common causes include transposition errors (e.g., recording $120 as $210), omission of an entry, incorrect posting to the wrong side of an account (debit instead of credit, or vice versa), or an error in calculating the account balances.

The process of correcting an unbalanced trial balance involves systematically reviewing the general ledger. This often includes checking individual transactions for accuracy, verifying that all entries have been posted correctly, and recalculating account balances. Specialized software often highlights potential discrepancies, aiding in the identification of errors. If the error cannot be easily identified, a more detailed investigation, potentially involving a re-examination of source documents and a reconciliation of bank statements, might be necessary. In some cases, professional assistance from an accountant may be required.

Visual Representation of Double-Entry Bookkeeping

Visual aids significantly enhance understanding of double-entry bookkeeping, a system where every financial transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining the accounting equation’s balance. Flowcharts and diagrams effectively illustrate this intricate process and the interconnectedness of accounts.

Double-Entry Bookkeeping Flowchart

This flowchart Artikels the steps involved in recording a transaction using the double-entry system. Each step ensures accuracy and the maintenance of the fundamental accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity).

[Start] -->

|

V

Identify the accounts affected -->

|

V

Determine the debit and credit accounts -->

|

V

Record the debit entry in the debit column of the affected account -->

|

V

Record the credit entry in the credit column of the affected account -->

|

V

Ensure the debit and credit amounts are equal -->

|

V

Post the entries to the general ledger -->

|

V

[End]

Diagram Showing the Relationship Between Accounts and the Accounting Equation

The following table visually represents how different account types affect the accounting equation. Increases and decreases in assets, liabilities, and equity are shown, demonstrating the interconnectedness within the double-entry system.

| Account Type | Increase | Decrease | Impact on Accounting Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assets (e.g., Cash, Accounts Receivable) | Debit | Credit | Increases Assets; increases either Liabilities or Equity to maintain balance |

| Liabilities (e.g., Accounts Payable, Loans Payable) | Credit | Debit | Increases Liabilities; increases Assets or decreases Equity to maintain balance |

| Equity (e.g., Owner’s Equity, Retained Earnings) | Credit | Debit | Increases Equity; increases Assets or decreases Liabilities to maintain balance |

| Revenue (e.g., Sales Revenue, Service Revenue) | Credit | Debit | Increases Equity (Retained Earnings); increases Assets to maintain balance |

| Expenses (e.g., Rent Expense, Salaries Expense) | Debit | Credit | Decreases Equity (Retained Earnings); decreases Assets to maintain balance |

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, must always remain balanced after every transaction. This balance is achieved through the dual nature of double-entry bookkeeping, where every debit has a corresponding credit.

Advanced Concepts (Optional)

This section delves into more complex aspects of double-entry bookkeeping, expanding upon the foundational principles already covered. Understanding these advanced concepts will allow for a more comprehensive and accurate representation of a business’s financial position. We will explore the differences between accrual and cash accounting, the vital role of subsidiary ledgers, and the handling of more intricate transactions like depreciation and bad debts.

Accrual Accounting versus Cash Accounting

Accrual accounting and cash accounting represent two distinct methods of recording financial transactions. Accrual accounting recognizes revenue when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, regardless of when cash changes hands. Cash accounting, conversely, records revenue and expenses only when cash is received or paid out. The choice between these methods significantly impacts the timing of revenue and expense recognition, ultimately influencing a company’s reported financial performance. Accrual accounting provides a more accurate reflection of a company’s financial performance over time, while cash accounting offers a simpler, more immediate picture of cash flow. For example, a company selling goods on credit under accrual accounting would record the revenue at the time of sale, even though payment might not be received for several weeks. Under cash accounting, the revenue would only be recorded when the cash is actually received.

Subsidiary Ledgers and Their Relationship to the General Ledger

Subsidiary ledgers are detailed records that provide specific information about individual accounts within a larger category. These detailed records are then summarized and posted to the general ledger, which provides a consolidated overview of all accounts. For example, a company might maintain a subsidiary ledger for accounts receivable, detailing the outstanding balances owed by each customer. The total of all balances in the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger should always equal the balance in the accounts receivable account in the general ledger. This ensures consistency and allows for efficient tracking of individual transactions while maintaining a concise overall view of the company’s financial position. This system of checks and balances helps prevent errors and ensures the accuracy of financial reporting.

Handling Complex Transactions: Depreciation and Bad Debts

Several transactions require more nuanced accounting treatments. Let’s examine depreciation and bad debts.

- Depreciation: Depreciation reflects the allocation of an asset’s cost over its useful life. For example, a company purchases a machine for $10,000 with a useful life of 5 years and a salvage value of $1,000. Annual depreciation expense would be ($10,000 – $1,000) / 5 = $1,800. This expense is recorded each year, reducing the asset’s book value and reflecting the gradual consumption of its economic benefit. Different depreciation methods (straight-line, declining balance, etc.) exist, each with its own calculation.

- Bad Debts: Bad debts represent accounts receivable that are unlikely to be collected. Companies estimate potential bad debts based on historical data or industry benchmarks. This estimate is recorded as an expense (Bad Debt Expense) and a contra-asset account (Allowance for Doubtful Accounts) is used to reduce the accounts receivable balance. For example, if a company estimates 5% of its $50,000 accounts receivable to be uncollectible, it would record a $2,500 bad debt expense and increase the allowance for doubtful accounts by $2,500. When a specific account is deemed uncollectible, it is written off against the allowance account.

Concluding Remarks

Mastering double-entry bookkeeping is crucial for anyone involved in financial management. By understanding the fundamental principles of debits and credits, the accounting equation, and the process of recording transactions, you’ll gain valuable insights into how businesses track their financial health. This guide has equipped you with the tools to confidently navigate the world of accounting, from simple journal entries to more complex financial statements. The clarity and practicality of the examples provided ensure that you can readily apply this knowledge to your own financial endeavors.

Expert Answers

What is the purpose of a trial balance?

A trial balance summarizes all debit and credit balances in the general ledger to ensure they are equal. This verifies the accuracy of the recording process.

What are adjusting entries and why are they necessary?

Adjusting entries update accounts at the end of an accounting period to reflect transactions that haven’t been fully recorded. This ensures financial statements accurately reflect the company’s financial position.

What’s the difference between accrual and cash accounting?

Accrual accounting records revenue when earned and expenses when incurred, regardless of cash flow. Cash accounting records transactions only when cash changes hands.

How do I handle bad debts using double-entry bookkeeping?

Bad debts are written off by debiting bad debt expense and crediting accounts receivable. This reduces both the expense and the amount owed to the company.