Common Financial Statement Errors and Fixes unveils the often-overlooked pitfalls in financial reporting. Accurate financial statements are the bedrock of sound business decisions, yet even minor errors can have significant consequences for stakeholders. This exploration delves into common mistakes across income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements, offering practical guidance on identification and correction. We’ll examine the root causes of these errors, explore preventative measures, and discuss the implications for various stakeholders, from investors to regulatory bodies. Understanding these issues is crucial for maintaining financial integrity and ensuring responsible financial management.

The journey through this guide will cover a range of topics, from recognizing errors in revenue recognition and expense classification to understanding the impact of misstated assets and liabilities. We will also analyze how ratio analysis can be a powerful tool in detecting anomalies and preventing fraud. Finally, we will provide practical steps for correcting errors and establishing robust internal controls to minimize future occurrences. This comprehensive approach ensures a thorough understanding of the entire process, from error identification to effective remediation.

Income Statement Errors

The income statement, a crucial financial statement, presents a company’s financial performance over a specific period. Accuracy is paramount; errors can lead to flawed business decisions and misrepresentation of financial health. This section details common income statement errors, their causes, and how to rectify them.

Revenue Recognition Errors

Accurate revenue recognition is fundamental to a reliable income statement. Common errors stem from prematurely recognizing revenue (before goods are delivered or services rendered) or inappropriately deferring revenue (delaying its recognition beyond the appropriate period). For example, a company might record revenue from a subscription service for the entire year upfront, even though the service is provided monthly. This inflates revenue in the initial period and understates it in subsequent periods. Conversely, a company might fail to recognize revenue from a long-term project until its final completion, thus understating revenue during the project’s progress. These discrepancies distort the company’s reported profitability and can mislead investors and creditors.

Impact of Expense Misclassification

Misclassifying expenses can significantly distort the income statement’s depiction of profitability. Expenses should be categorized appropriately as either cost of goods sold (COGS), operating expenses, or other expenses. For example, classifying salaries of sales staff as administrative expenses instead of selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses will misrepresent the true cost of sales and the company’s operating efficiency. Similarly, capital expenditures (like purchasing equipment) should be capitalized and depreciated over their useful life rather than expensed immediately, which would artificially reduce net income in the year of purchase. This misclassification impacts key financial ratios and can hinder accurate performance analysis.

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) Calculation Errors

Errors in calculating COGS directly affect gross profit and net income. Common errors include inaccurate inventory counts (leading to either overstatement or understatement of COGS), incorrect valuation of inventory (using inappropriate costing methods like FIFO or LIFO incorrectly), and improper allocation of manufacturing overhead costs to COGS. For instance, if a company undercounts its ending inventory, it will overstate COGS, thereby understating gross profit and net income. Conversely, overstating ending inventory will understate COGS, leading to an overstatement of gross profit and net income. These errors directly affect the profitability metrics used for business evaluation.

Common Income Statement Errors, Causes, and Corrective Actions

| Error | Cause | Corrective Action | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Revenue Recognition | Improper application of revenue recognition principles | Adjust revenue to reflect the point in time when performance obligations are satisfied | Recognizing revenue for a software license before delivery |

| Expense Misclassification | Lack of clear accounting policies or inadequate training | Review and revise the chart of accounts, ensure proper expense categorization | Classifying research and development costs as selling expenses |

| Incorrect COGS Calculation | Inaccurate inventory counts or valuation | Conduct thorough inventory counts and utilize appropriate inventory costing methods (FIFO, LIFO, weighted-average) | Undercounting ending inventory, leading to overstated COGS |

| Incorrect Depreciation Calculation | Using an inappropriate depreciation method or useful life | Review asset useful lives and select the appropriate depreciation method | Using straight-line depreciation for an asset with declining value |

| Omission of Expenses | Oversight or intentional misrepresentation | Thorough review of all transactions and supporting documentation | Failing to record rent expense |

Balance Sheet Errors: Common Financial Statement Errors And Fixes

The balance sheet, a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time, is susceptible to various errors that can significantly distort its accuracy and usefulness. These errors can stem from incorrect valuations, misclassifications, or flawed accounting practices, ultimately impacting crucial financial ratios and decision-making processes. Understanding common balance sheet errors and their consequences is crucial for maintaining financial integrity.

Asset Valuation Errors

Accurate asset valuation is paramount for a reliable balance sheet. Common errors include overvaluing assets, particularly intangible assets like goodwill or intellectual property, leading to an inflated net asset value. Conversely, undervaluing assets, like property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) due to outdated depreciation methods or neglecting obsolescence, can understate the company’s true worth. For instance, a company might overestimate the value of its brand name without proper market research, resulting in an inflated asset value on the balance sheet. Similarly, using a straight-line depreciation method for equipment that experiences rapid technological obsolescence will undervalue the asset over its useful life. These valuation discrepancies can mislead investors and creditors regarding the company’s financial health.

Liabilities Classification Errors

Improper classification of liabilities can lead to misinterpretations of a company’s financial obligations and solvency. For example, classifying a short-term liability as long-term can artificially inflate the company’s liquidity ratios, masking potential short-term financial distress. Conversely, misclassifying a long-term liability as short-term can create a false impression of immediate financial pressure. The consequences of such misclassifications can range from inaccurate financial reporting to difficulties in securing loans or attracting investors. A company failing to properly distinguish between current and non-current liabilities might present a misleading picture of its ability to meet its immediate obligations.

Equity Accounting Errors

Errors in equity accounting, such as incorrect recording of retained earnings or improperly accounting for stock transactions, can directly impact the balance sheet’s equity section. For example, failing to adjust retained earnings for prior-period errors can lead to a cumulative misstatement of equity. Similarly, inaccurate recording of treasury stock transactions can distort the presentation of shareholders’ equity. These errors can affect key financial ratios and investor confidence, potentially leading to inaccurate valuations and misinformed investment decisions. A classic example would be the incorrect recording of dividends paid, which would directly affect the retained earnings and overall equity balance.

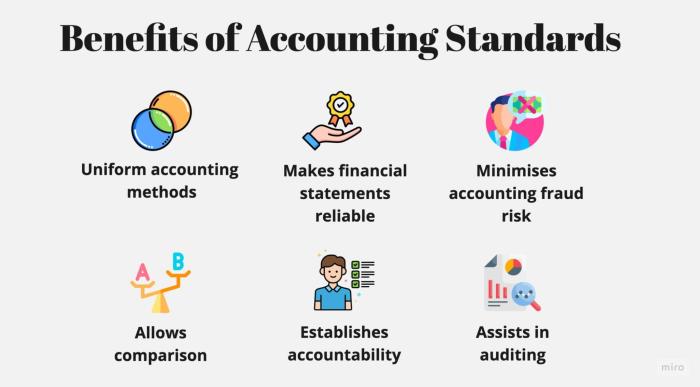

Best Practices for Preventing Balance Sheet Errors

Preventing balance sheet errors requires a combination of diligent practices and robust internal controls. A well-defined accounting policy manual, regular internal audits, and employee training are crucial.

- Implement a robust internal control system to ensure accuracy and prevent fraud.

- Regularly reconcile bank statements and other accounts.

- Use standardized valuation methods for assets and liabilities.

- Maintain detailed documentation supporting all balance sheet entries.

- Conduct periodic reviews of the balance sheet to identify and correct any discrepancies.

- Engage external auditors to provide independent verification of financial statements.

- Utilize accounting software with built-in error checks and validation rules.

- Provide ongoing training to accounting staff on proper accounting procedures and standards.

Cash Flow Statement Errors

The cash flow statement, unlike the income statement and balance sheet, focuses on the movement of cash within a business over a period. Errors in this statement can significantly distort a company’s liquidity position and its ability to meet its short-term and long-term obligations. Understanding common errors and their corrections is crucial for accurate financial reporting and analysis.

Classifying Cash Flows from Operating Activities, Common Financial Statement Errors and Fixes

Incorrect classification of cash flows is a frequent error. Operating activities represent the cash inflows and outflows directly related to a company’s core business operations. For example, cash received from customers is an inflow, while cash paid to suppliers is an outflow. However, errors arise when items are miscategorized. A common mistake is classifying interest payments as operating activities when they are, in fact, financing activities. Similarly, dividend income might be incorrectly included in operating activities rather than investing activities. Another example is the inclusion of capital expenditures (CapEx) in operating activities; CapEx, being a significant investment, should be classified under investing activities. These misclassifications can lead to an overstated or understated net cash flow from operating activities, providing a misleading picture of the company’s operational efficiency.

Errors in Reporting Investing and Financing Activities

Investing activities involve changes in long-term assets, such as property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), and investments in other companies. Financing activities relate to how a company raises capital, including debt and equity financing. Errors in these sections often stem from a lack of understanding of the underlying transactions. For instance, proceeds from issuing bonds should be classified as financing activities, while the purchase of a competitor’s company should be classified as an investing activity. A common mistake is the misclassification of repayments of long-term debt; this is clearly a financing activity. Conversely, the purchase of marketable securities is an investing activity, and misclassifying it as an operating activity would significantly distort the statement. The key distinction lies in understanding the nature of the transaction and its impact on the company’s long-term assets and capital structure.

Correctly Preparing a Cash Flow Statement

A step-by-step procedure for correctly preparing a cash flow statement ensures accuracy and consistency.

- Determine the net cash flow from operating activities: Start with net income and adjust it for non-cash items such as depreciation and amortization, changes in working capital (accounts receivable, accounts payable, inventory), and gains or losses on the sale of assets. Use the direct or indirect method, ensuring consistency in application.

- Identify cash flows from investing activities: This section includes cash inflows from the sale of long-term assets and cash outflows from the purchase of long-term assets, investments in securities, and loans to other entities.

- Identify cash flows from financing activities: This section includes cash inflows from issuing debt or equity and cash outflows from debt repayments, dividend payments, and repurchasing of company stock.

- Calculate the net increase or decrease in cash: Sum the net cash flows from operating, investing, and financing activities. This should reconcile with the change in the cash balance on the balance sheet.

- Reconcile the beginning and ending cash balances: The net increase or decrease in cash, added to the beginning cash balance, should equal the ending cash balance. This provides a crucial check on the accuracy of the entire statement.

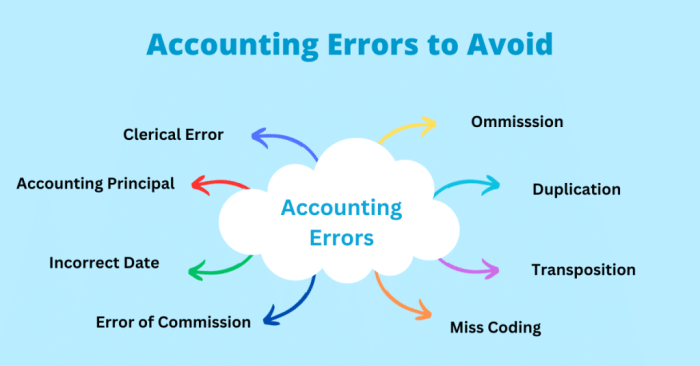

Errors in Financial Statement Presentation

Inconsistent formatting and unclear disclosures are common culprits behind misinterpretations of financial statements. These errors can range from minor stylistic inconsistencies to deliberate attempts to mislead users, ultimately impacting decision-making based on flawed information. Understanding how to identify and correct these presentation errors is crucial for accurate financial reporting.

Inconsistent formatting can significantly hinder the readability and understanding of financial statements. For example, using different fonts, sizes, or styles inconsistently throughout the statement can create confusion and make it difficult to compare figures across periods or line items. Similarly, inconsistent use of currency symbols, decimal places, or accounting terminology can lead to misinterpretations and errors in analysis. The lack of a standardized presentation makes it harder for users to quickly grasp the key financial information.

Misleading Presentations and their Impact

Misleading presentations can arise from various intentional or unintentional actions. For instance, strategically placing certain information in less prominent areas, using ambiguous language in disclosures, or manipulating the visual representation of data (e.g., using misleading graphs or charts) can create a distorted picture of a company’s financial health. These actions can lead to inaccurate assessments of profitability, solvency, and liquidity, resulting in poor investment decisions or misguided strategic planning by stakeholders. For example, a company might selectively highlight positive aspects while downplaying or obscuring negative ones, leading investors to make an overly optimistic assessment of the company’s prospects. Conversely, inconsistent application of accounting standards can lead to unintentional misrepresentations, undermining the reliability of the financial statements.

Importance of Clear and Concise Disclosures

Clear and concise disclosures are vital for transparent financial reporting. They provide essential context for the numbers presented in the financial statements, helping users understand the underlying transactions and events that shaped the company’s financial performance. Adequate disclosures explain the accounting policies used, any significant accounting changes, and any unusual or complex transactions. Without sufficient disclosures, users might misinterpret the figures, leading to incorrect conclusions. For example, a change in accounting method for inventory valuation should be clearly disclosed along with its impact on reported profits. Similarly, any significant legal disputes or contingent liabilities should be fully disclosed to provide a complete picture of the company’s financial position.

Proper Presentation of Key Financial Statement Elements

A well-presented financial statement employs consistent formatting and clear labeling. The following table illustrates proper presentation:

| Element | Income Statement | Balance Sheet | Cash Flow Statement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heading | Company Name Income Statement For the Year Ended [Date] |

Company Name Balance Sheet As of [Date] |

Company Name Statement of Cash Flows For the Year Ended [Date] |

| Units | Currency (e.g., USD) | Currency (e.g., USD) | Currency (e.g., USD) |

| Format | Clearly labeled sections (Revenue, COGS, Expenses, Net Income) | Assets, Liabilities, and Equity clearly separated and totaled | Operating, Investing, and Financing activities clearly separated |

| Footnotes | Explanations of significant line items | Explanations of significant line items | Explanations of significant line items |

Ratio Analysis and Error Detection

Ratio analysis offers a powerful tool for detecting potential errors and inconsistencies within financial statements. By examining the relationships between various line items, analysts can identify anomalies that might indicate errors, omissions, or even fraudulent activities. This analytical approach goes beyond simply reviewing individual figures and provides a more holistic understanding of a company’s financial health.

Ratio analysis works by comparing different financial statement accounts to reveal trends and patterns. Significant deviations from historical trends, industry benchmarks, or expected relationships between accounts can signal potential problems. For example, a sudden and dramatic increase in accounts receivable coupled with a stagnant sales figure might indicate issues with credit collection or even fictitious sales.

Identifying Potential Errors Through Ratio Analysis

Unusual or unexpected ratios can be strong indicators of errors. Consider the current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities). A significantly low current ratio might suggest that a company is struggling to meet its short-term obligations, potentially due to errors in the valuation of current assets or underreporting of current liabilities. Conversely, an unusually high current ratio might indicate an inefficient use of working capital, potentially stemming from overstatement of assets or understatement of liabilities. Analyzing the trend of this ratio over several periods is crucial, allowing for a better understanding of the underlying reasons for any changes.

Interpreting Unusual Ratios: Examples

Let’s examine the gross profit margin (Gross Profit / Revenue). A consistent decline in the gross profit margin, despite stable or increasing sales, could signal several issues. This could be caused by errors in cost of goods sold calculations (e.g., overstating inventory), or it could indicate pricing pressures or a decline in product quality. Similarly, a significant increase in the debt-to-equity ratio (Total Debt / Total Equity) could indicate excessive borrowing, potentially masking underlying financial weaknesses or reflecting errors in the reporting of liabilities. A thorough investigation would be required to determine the root cause.

Ratio Analysis and Fraud Detection

Ratio analysis can also be a valuable tool in detecting potential fraudulent activities. For instance, a persistently high inventory turnover ratio (Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory) combined with a low gross profit margin might suggest inventory theft or fictitious sales. The high turnover implies rapid sales, but the low margin suggests something is amiss with the pricing or costing of the goods sold. Another example involves an unusual increase in accounts receivable coupled with a high percentage of bad debts. This combination could indicate fictitious sales, where invoices are created but no actual transactions occur. The high percentage of bad debts masks the fraud by suggesting legitimate sales that later proved uncollectible. These are just a few illustrations; a comprehensive analysis requires consideration of multiple ratios in conjunction with other qualitative factors.

Internal Controls and Error Prevention

Robust internal controls are crucial for minimizing financial statement errors and ensuring the reliability of financial reporting. A well-designed system acts as a safeguard against fraud, human error, and system failures, leading to more accurate and trustworthy financial information. This section explores key components of effective internal control systems and their role in preventing errors.

A strong internal control system encompasses various procedures and policies designed to mitigate risks and ensure the accuracy and reliability of financial data. It’s not merely a set of rules, but a dynamic process requiring constant monitoring and adaptation to changes within the organization and its environment. The effectiveness of the system hinges on its design, implementation, and ongoing monitoring.

Find out about how How to Conduct a Financial Audit for Small Businesses can deliver the best answers for your issues.

Segregation of Duties

Segregation of duties is a fundamental principle of internal control. It involves dividing tasks among different individuals to prevent any single person from having complete control over a process. This prevents fraud and errors by requiring checks and balances at each stage. For example, the person responsible for receiving payments should not also be the person responsible for recording those payments in the accounting system. This division of responsibility ensures that errors or fraudulent activities are more likely to be detected. Without segregation of duties, an employee could potentially embezzle funds or manipulate records without detection. The effectiveness of segregation of duties is directly proportional to the level of separation between different stages of a transaction. For instance, separating authorization, recording, and custody functions is more effective than simply separating two of them.

Regular Reconciliations

Regular reconciliations are a critical component of internal control. This involves comparing internal records to external statements or data sources to identify discrepancies. Bank reconciliations, for example, compare the company’s cash balance per its books to the bank statement balance. This process helps to detect errors in recording transactions, unrecorded transactions, or potential fraud. Other important reconciliations include accounts receivable and accounts payable reconciliations. Discrepancies uncovered during reconciliation should be promptly investigated and corrected. The frequency of reconciliations depends on the volume of transactions and the materiality of the accounts; high-volume accounts or those with a higher risk of error require more frequent reconciliations.

Importance of Audits

Regular audits, both internal and external, provide an independent assessment of the effectiveness of internal controls and the accuracy of financial statements. Internal audits are conducted by the company’s own internal audit department, while external audits are conducted by independent accounting firms. These audits involve examining financial records, evaluating internal controls, and testing the accuracy of financial reporting. A well-executed audit can identify weaknesses in internal controls, uncover errors or fraud, and provide assurance to stakeholders that the financial statements are reliable. The frequency of audits is often determined by factors such as company size, industry regulations, and the complexity of the business operations. For publicly traded companies, annual external audits are mandatory.

Impact of Errors on Stakeholders

Financial statement errors, regardless of size or intention, have far-reaching consequences for a wide range of stakeholders. The accuracy and reliability of these statements are fundamental to informed decision-making, and errors can erode trust, leading to significant financial and reputational damage. This section examines the impact of such errors on key stakeholder groups.

Consequences for Investors

Errors in financial statements directly impact investors’ ability to make sound investment decisions. Overstated profits, for instance, might lure investors into overvaluing a company’s stock, leading to substantial losses when the truth is revealed. Conversely, understated profits or hidden liabilities can cause investors to undervalue a company, missing out on potential gains. Material misstatements can lead to lawsuits from investors who suffered financial losses due to reliance on inaccurate information. For example, the Enron scandal, where accounting irregularities significantly misrepresented the company’s financial health, resulted in billions of dollars in losses for investors and widespread legal repercussions. The impact extends beyond immediate financial losses; it can also damage investor confidence in the market as a whole.

Implications for Creditors and Lenders

Creditors and lenders rely heavily on financial statements to assess a company’s creditworthiness and repayment ability. Inaccurate financial information can lead to incorrect credit risk assessments. If a company’s debt levels are understated, lenders might extend more credit than is prudent, increasing their risk of default. Conversely, if assets are overstated, a lender might be misled into believing the company has more collateral than it actually does. This could lead to significant losses for the lender if the borrower defaults. The consequences can be severe, potentially leading to bankruptcy for both the borrowing company and the lender in extreme cases.

Legal and Regulatory Ramifications of Errors

The legal and regulatory consequences of financial statement errors can be severe. Depending on the nature and extent of the errors, companies and individuals responsible can face penalties ranging from fines to criminal charges. Securities laws often impose strict liability for material misstatements, even if unintentional. Regulatory bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States actively investigate and prosecute cases of financial statement fraud. Furthermore, companies may face delisting from stock exchanges, damage to their reputation, and difficulty securing future financing. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, enacted in response to major accounting scandals, significantly strengthened corporate governance and accounting oversight to mitigate such risks. Non-compliance can lead to substantial penalties and legal battles.

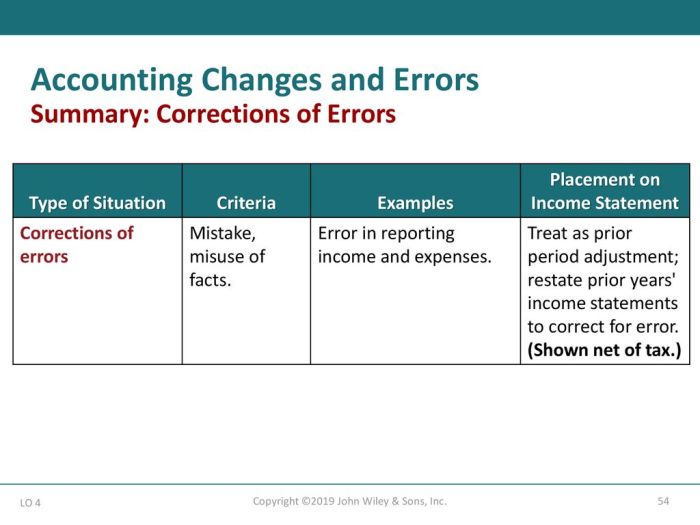

Correcting Financial Statement Errors

Correcting errors in financial statements is crucial for maintaining the accuracy and reliability of a company’s financial reporting. These corrections ensure that stakeholders receive a true and fair view of the company’s financial position and performance. Failure to correct errors can lead to misinformed decisions and potentially legal repercussions. The process involves identifying the error, determining the appropriate accounting treatment, and adjusting the financial statements accordingly.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Correcting Errors

The process of correcting errors generally follows a structured approach. First, the error must be thoroughly investigated and identified. This involves reviewing the original transaction documentation and comparing it to the recorded entries in the accounting system. Once the error is pinpointed, its nature and materiality should be assessed. Materiality refers to whether the error is significant enough to affect the decisions of users of the financial statements. Finally, the appropriate correcting journal entry is prepared and posted, updating the affected accounts and ensuring the financial statements accurately reflect the corrected information. Subsequent financial statements should then be adjusted to reflect the correction.

Accounting Treatment for Correcting Errors

The accounting treatment for correcting errors depends on the nature and timing of the error. Errors discovered before the financial statements are issued are typically corrected by adjusting the entries in the general ledger. This is done through a correcting journal entry that reverses the incorrect entry and records the correct one. For errors discovered after the financial statements are issued, the correction is typically made through a prior period adjustment. This involves restating the prior period’s financial statements to reflect the corrected information and disclosing the nature and impact of the adjustment in the current period’s financial statements. For immaterial errors, they may be corrected in the current period without restating prior periods.

Impact of Corrections on Subsequent Financial Statements

The impact of error corrections on subsequent financial statements will vary depending on the nature and size of the error. For example, correcting an error in revenue recognition will affect the income statement, the retained earnings statement, and the balance sheet. The correction will adjust the reported revenue for the period in which the error occurred and also affect the retained earnings balance and the balance sheet’s equity section. The impact will be visible in the corrected financial statements and the accompanying notes to the financial statements, which will clearly disclose the nature and impact of the error correction. Any changes to the prior periods’ statements will flow through to the current period’s retained earnings, and thus, equity. Consistent and accurate reporting is critical for maintaining financial statement integrity.

Illustrative Examples of Common Errors

Understanding common financial statement errors is crucial for accurate financial reporting and analysis. These examples highlight typical mistakes across the three core financial statements, along with their corrections. The goal is to illustrate how seemingly small errors can significantly impact financial outcomes and decision-making.

Income Statement Errors

Incorrect revenue recognition is a frequent error. For example, recording revenue before goods are shipped or services rendered inflates current period income and understates future periods. Similarly, expenses may be incorrectly capitalized, meaning they are treated as assets rather than immediate expenses, leading to an overstatement of net income.

- Example 1: Premature Revenue Recognition: A company records $100,000 in sales revenue in December for goods to be shipped in January. This incorrectly boosts December’s net income. Corrective Action: The $100,000 should be recorded as a deferred revenue liability on the balance sheet in December and recognized as revenue in January when the goods are shipped.

- Example 2: Expense Capitalization Error: A company incorrectly capitalizes $50,000 in research and development costs as an asset instead of expensing them. This artificially inflates net income in the current year. Corrective Action: The $50,000 should be expensed on the income statement, reducing net income for the current period.

Balance Sheet Errors

Errors on the balance sheet often stem from incorrect asset valuation or liability classification. For instance, understating accounts receivable or overstating inventory can distort the company’s true financial position. Similarly, misclassifying liabilities as short-term or long-term can impact the assessment of a company’s liquidity.

- Example 1: Inventory Overstatement: A company overstates its ending inventory by $20,000. This directly inflates the value of assets on the balance sheet. Corrective Action: Reduce the inventory value by $20,000, and adjust the cost of goods sold on the income statement to reflect the accurate inventory valuation. This will lower net income.

- Example 2: Accounts Payable Understatement: A company fails to record $15,000 in accounts payable. This understates liabilities and thus overstates equity. Corrective Action: Record the $15,000 accounts payable, reducing retained earnings and correcting the balance sheet’s equity section.

Cash Flow Statement Errors

Errors in the cash flow statement frequently involve misclassifying cash flows between operating, investing, and financing activities. For example, capital expenditures might be incorrectly classified as operating cash outflows, distorting the analysis of a company’s operational efficiency. Similarly, dividend payments could be incorrectly reported under investing activities instead of financing activities.

- Example 1: Misclassification of Capital Expenditure: A company incorrectly classifies a $30,000 purchase of equipment as an operating cash outflow. This misrepresents the company’s investment activities. Corrective Action: Reclassify the $30,000 as a cash outflow from investing activities.

- Example 2: Incorrect Classification of Dividends Paid: A company reports $25,000 in dividends paid as an investing activity instead of a financing activity. This misleads analysts regarding the company’s financing decisions. Corrective Action: Reclassify the $25,000 dividend payment as a cash outflow from financing activities.

Final Thoughts

Mastering the art of accurate financial statement preparation is paramount for any organization. By understanding the common errors discussed, implementing robust internal controls, and leveraging tools like ratio analysis, businesses can significantly reduce the risk of costly mistakes. The information provided here serves as a valuable resource for improving financial reporting accuracy, mitigating potential risks, and ultimately fostering greater financial transparency and accountability. Remember, proactive error prevention is far more efficient than reactive correction. Regular review, diligent attention to detail, and a commitment to accuracy are key to achieving financial health and success.

Clarifying Questions

What are the legal ramifications of significant financial statement errors?

Significant errors can lead to legal action from investors, lawsuits, fines from regulatory bodies (like the SEC), and even criminal charges in cases of fraud.

How often should financial statements be reconciled?

Ideally, reconciliations should be performed monthly to catch errors early. More frequent reconciliations are better for high-volume transactions.

Can small errors be ignored?

No, even small errors can accumulate and distort the overall financial picture. Addressing all errors promptly is crucial for accuracy.

What is the role of an external auditor in preventing errors?

External auditors provide an independent assessment of financial statements, helping identify potential errors and weaknesses in internal controls.