Accounting Basics: Everything You Need to Know. Understanding the financial health of any entity, be it a multinational corporation or a small bakery, hinges on grasping fundamental accounting principles. This guide unravels the complexities of accounting, transforming what might seem like an intimidating subject into a clear and accessible framework for understanding financial information. We’ll explore core concepts, from the accounting equation to financial statement analysis, empowering you to interpret financial data and make informed decisions.

This exploration will cover the essential elements of accounting, including the accounting equation, debits and credits, the accounting cycle, and the creation and interpretation of key financial statements. We’ll delve into generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and explore how they influence financial reporting. Practical examples and real-world applications will reinforce your understanding, ensuring you leave with a solid foundation in accounting basics.

Introduction to Accounting Basics

Accounting is the systematic recording, analyzing, and interpreting of financial transactions. It provides a comprehensive picture of an organization’s financial health, enabling informed decision-making by stakeholders such as owners, managers, investors, and creditors. Understanding the basics of accounting is crucial for anyone involved in business or personal finance.

Accounting’s purpose is to provide financial information that is useful for various decision-making processes. This information helps track the financial performance of a business, assess its financial position, and predict future financial outcomes. Accurate and timely accounting data is vital for effective resource allocation, planning, and control.

Fundamental Accounting Concepts

Several core principles underpin the practice of accounting. These principles ensure consistency and reliability in the presentation of financial information. Understanding these concepts is fundamental to grasping the overall process. For example, the going concern principle assumes a business will continue operating for the foreseeable future, influencing how assets and liabilities are valued. The accrual principle dictates that revenue and expenses are recognized when earned or incurred, regardless of when cash changes hands. The matching principle links expenses to the revenues they generate within the same accounting period. Finally, the consistency principle suggests that once an accounting method is chosen, it should be applied consistently over time to allow for meaningful comparisons across periods.

Types of Accounting

Accounting is broadly categorized into two main types: financial accounting and managerial accounting. Financial accounting focuses on creating reports for external users, such as investors and creditors. These reports, including the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement, adhere to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Managerial accounting, on the other hand, is used internally by management to make strategic and operational decisions. It utilizes various techniques like budgeting, cost accounting, and performance analysis, often tailored to the specific needs of the organization and not bound by the same strict reporting standards as financial accounting.

Examples of Accounting in Various Industries

Accounting is vital across all industries. In the retail sector, accounting tracks sales, inventory levels, and costs of goods sold to determine profitability and manage cash flow. Manufacturing companies use accounting to track production costs, analyze efficiency, and determine pricing strategies. In the healthcare industry, accounting is crucial for managing patient billing, insurance reimbursements, and overall hospital or clinic finances. The financial services industry, including banks and investment firms, relies heavily on accounting for risk management, regulatory compliance, and investment analysis. Even non-profit organizations utilize accounting to track donations, manage expenses, and demonstrate their financial accountability to donors and the public.

The Accounting Equation

The foundation of accounting rests on a simple yet powerful equation: the accounting equation. Understanding this equation is crucial for grasping the basic principles of financial record-keeping and analysis. It provides a framework for understanding the relationship between a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity.

The accounting equation states that a company’s assets are always equal to the sum of its liabilities and equity. This fundamental relationship reflects the basic concept of double-entry bookkeeping, where every transaction affects at least two accounts. This ensures that the accounting equation always remains balanced. This balance is a key indicator of the accuracy of the financial records.

Components of the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation consists of three core components: assets, liabilities, and equity. Each represents a different aspect of a company’s financial position.

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Assets are what a company owns, representing resources controlled by the company as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity. Liabilities represent obligations to others, representing the company’s debts or financial obligations. Equity represents the owners’ stake in the company, representing the residual interest in the assets of the entity after deducting all its liabilities.

Examples of Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

Let’s illustrate these components with some concrete examples.

Assets might include cash, accounts receivable (money owed to the company), inventory (goods held for sale), equipment, buildings, and land. Liabilities could encompass accounts payable (money owed by the company), loans payable, salaries payable, and taxes payable. Equity includes common stock (the investment made by shareholders), retained earnings (accumulated profits reinvested in the business), and additional paid-in capital.

Transaction Effects on the Accounting Equation

Every financial transaction impacts the accounting equation, maintaining its balance. Consider a simple example: a company borrows $10,000 from a bank. This transaction increases the company’s assets (cash) by $10,000 and simultaneously increases its liabilities (loans payable) by $10,000. The equation remains balanced because both sides increased by the same amount. Another example is a company selling goods for $5,000 cash. This increases cash (an asset) and increases retained earnings (equity).

Types of Asset, Liability, and Equity Accounts

The following table categorizes different types of accounts within each component of the accounting equation.

| Assets | Liabilities | Equity |

|---|---|---|

| Cash | Accounts Payable | Common Stock |

| Accounts Receivable | Notes Payable | Retained Earnings |

| Inventory | Salaries Payable | Treasury Stock |

| Equipment | Taxes Payable | Additional Paid-in Capital |

Debits and Credits

Understanding debits and credits is fundamental to double-entry bookkeeping. This system ensures that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) always remains balanced. Every transaction affects at least two accounts, with one receiving a debit and the other a credit. The key is understanding how debits and credits impact different account types.

Debits increase the balance of some accounts and decrease the balance of others. Credits work in the opposite way. This seemingly simple concept is the cornerstone of accurate financial record-keeping. The effect of a debit or credit depends entirely on the type of account.

Debit and Credit Rules

The basic rule is that debits increase asset, expense, and dividend accounts, while credits increase liability, equity, and revenue accounts. Conversely, credits decrease asset, expense, and dividend accounts, while debits decrease liability, equity, and revenue accounts. Remembering this core principle is crucial for accurate bookkeeping. Think of it this way: Debits increase what the business *owns* (assets) or *uses* (expenses and dividends), while credits increase what the business *owes* (liabilities) or *earns* (revenue and equity).

Examples of Debit and Credit Entries

Let’s illustrate with examples. Suppose a company purchases office equipment for $1,000 cash. This transaction involves two accounts: Office Equipment (an asset) and Cash (an asset). The debit increases the Office Equipment account by $1,000, reflecting the increase in assets. The credit decreases the Cash account by $1,000, reflecting the decrease in assets. The accounting equation remains balanced because the increase in one asset is offset by a decrease in another.

Another example: The company provides services to a client and receives $500 in cash. This transaction affects two accounts: Cash (an asset) and Service Revenue (an equity account). The debit increases the Cash account by $500. The credit increases the Service Revenue account by $500, reflecting the increase in equity due to earned revenue. Again, the accounting equation remains balanced.

Debit and Credit Entries for Different Account Types

The impact of debits and credits varies depending on the account type. Assets normally have debit balances, meaning debits increase them and credits decrease them. Liabilities and Equity normally have credit balances, meaning credits increase them and debits decrease them. Expenses have debit balances, and revenues have credit balances. Dividends, representing distributions to shareholders, also have debit balances.

Common Accounts and Normal Balances

The following table summarizes common account types and their normal balances:

| Account Type | Normal Balance |

|---|---|

| Assets | Debit |

| Liabilities | Credit |

| Equity | Credit |

| Revenue | Credit |

| Expenses | Debit |

| Dividends | Debit |

The Accounting Cycle

The accounting cycle is a series of steps businesses follow to record, classify, summarize, and report their financial transactions. It’s a crucial process ensuring accurate financial statements and providing valuable insights into a company’s financial health. Understanding the accounting cycle is fundamental for anyone involved in financial management.

The accounting cycle’s purpose is to systematically process all financial transactions from the initial recording to the final presentation of financial statements. This systematic approach minimizes errors, facilitates efficient financial reporting, and provides a reliable basis for decision-making. Each step builds upon the previous one, creating a continuous flow of information.

Identifying and Recording Transactions

This initial step involves identifying all financial transactions that impact the business. This includes sales, purchases, expenses, and other relevant activities. Each transaction is then recorded using a source document, such as an invoice, receipt, or bank statement. For example, a sale of goods would be recorded using a sales invoice, detailing the goods sold, the customer, and the amount received. This detailed record-keeping forms the foundation for the entire accounting cycle.

Journalizing Transactions

Once transactions are identified and documented, they are recorded in a journal. The journal is a chronological record of all transactions, showing the accounts affected and the amounts involved. This process, called journalizing, uses debits and credits to maintain the accounting equation. For example, the sale of goods mentioned above would be journalized with a debit to Accounts Receivable (if credit sale) or Cash (if cash sale) and a credit to Sales Revenue.

Posting to the Ledger

After journalizing, the information is transferred from the journal to the general ledger. The general ledger is a collection of accounts that summarizes all transactions affecting each account. This process, called posting, organizes the data for easier analysis. For example, all entries related to Accounts Receivable would be posted to the Accounts Receivable account in the general ledger. This step provides a detailed view of each account’s balance.

Preparing a Trial Balance

A trial balance is a summary of all the general ledger accounts. It lists the debit and credit balances of each account. The purpose is to ensure that the total debits equal the total credits, maintaining the fundamental accounting equation. If there’s an imbalance, it indicates an error that needs to be identified and corrected before proceeding to the next steps. A trial balance serves as a checkpoint in the accounting cycle.

Preparing Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries are made at the end of an accounting period to update accounts and ensure that revenues and expenses are accurately reported. These entries adjust accounts for items like accrued expenses, prepaid expenses, unearned revenues, and accrued revenues. For example, if a company has incurred salaries but hasn’t yet paid them, an adjusting entry would debit Salaries Expense and credit Salaries Payable. This ensures expenses are correctly reflected in the period they were incurred.

Preparing Financial Statements

After making adjusting entries, the adjusted trial balance is used to prepare the financial statements. These statements include the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows. The income statement shows revenues and expenses, resulting in net income or net loss. The balance sheet presents the company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. The statement of cash flows summarizes cash inflows and outflows. These statements provide a comprehensive overview of the company’s financial performance and position.

Closing the Books

The closing process transfers the balances of temporary accounts (revenues, expenses, and dividends) to retained earnings. This resets these accounts to zero for the next accounting period. Closing entries are journalized and posted to the ledger, preparing the books for the new accounting period. This ensures a clean start for the next cycle.

Flowchart Illustrating the Accounting Cycle

A flowchart would visually represent the accounting cycle as a sequence of steps. It would begin with “Identify and Record Transactions,” followed by “Journalize Transactions,” then “Post to the Ledger,” “Prepare a Trial Balance,” “Prepare Adjusting Entries,” “Prepare Financial Statements,” and finally, “Closing the Books.” Arrows would connect each step, illustrating the sequential nature of the process. Each step could be represented by a rectangle, with the final step indicating the completion of one accounting cycle and the start of a new one.

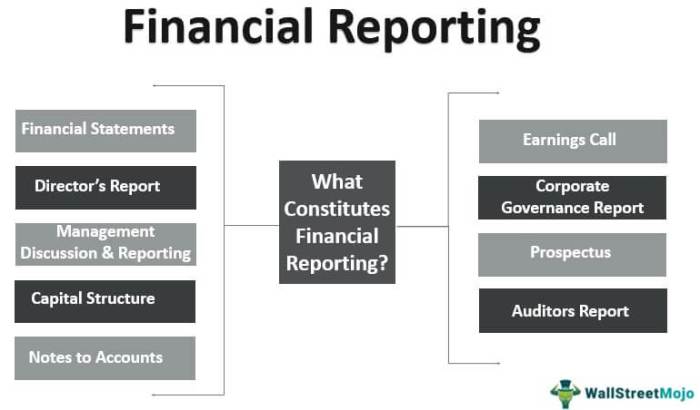

Financial Statements

Financial statements are the cornerstone of understanding a company’s financial health. They provide a structured summary of a business’s financial performance, position, and cash flows over a specific period. Three primary statements – the Income Statement, the Balance Sheet, and the Cash Flow Statement – work together to paint a comprehensive picture.

Income Statement

The Income Statement, also known as the Profit and Loss (P&L) statement, reports a company’s financial performance over a period of time, typically a quarter or a year. It summarizes revenues, costs, and expenses to arrive at net income or net loss. A simple Income Statement shows revenue less the cost of goods sold (COGS) resulting in gross profit. Further deductions of operating expenses (rent, salaries, utilities) lead to operating income. Finally, other income and expenses (interest, taxes) are considered to determine the net income or loss.

For example, imagine a small bakery. Their revenue might be $100,000 in sales for the year. Their COGS (flour, sugar, etc.) might be $30,000, resulting in a gross profit of $70,000. Operating expenses (rent, wages, utilities) total $40,000, leaving an operating income of $30,000. After accounting for taxes and interest, their net income might be $25,000. This shows profitability over the specified period.

Balance Sheet

The Balance Sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. It follows the fundamental accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

. Assets represent what a company owns (cash, accounts receivable, inventory, equipment). Liabilities represent what a company owes (accounts payable, loans). Equity represents the owners’ stake in the company (retained earnings, contributed capital). The balance sheet always balances; the total value of assets must equal the sum of liabilities and equity.

Consider the bakery example again. Their assets might include $5,000 in cash, $10,000 in accounts receivable (money owed to them), $20,000 in inventory, and $50,000 in equipment. Their liabilities might be $15,000 in accounts payable (money they owe to suppliers) and a $20,000 bank loan. Their equity would then be calculated as: Assets ($85,000) – Liabilities ($35,000) = Equity ($50,000). This shows the bakery’s financial position at a specific moment.

Cash Flow Statement

The Cash Flow Statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a period of time. It categorizes cash flows into three main activities: operating activities (cash from day-to-day business), investing activities (cash from buying or selling assets), and financing activities (cash from borrowing, issuing stock, or paying dividends). This statement helps assess a company’s liquidity and its ability to meet its short-term obligations.

Returning to the bakery, their operating activities might show positive cash flow from sales. Investing activities might show negative cash flow if they purchased new ovens. Financing activities might show positive cash flow if they took out a loan. The statement would detail the net increase or decrease in cash during the period, providing insight into the bakery’s cash management.

Comparison of Financial Statements

| Feature | Income Statement | Balance Sheet | Cash Flow Statement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | Over a period (e.g., year, quarter) | At a specific point in time | Over a period (e.g., year, quarter) |

| Primary Focus | Profitability | Financial Position | Cash Flows |

| Key Metrics | Revenue, Expenses, Net Income | Assets, Liabilities, Equity | Operating, Investing, Financing Cash Flows |

Basic Accounting Principles

Sound accounting practices rely on a set of established guidelines known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). These principles ensure consistency, reliability, and comparability in financial reporting, allowing stakeholders to make informed decisions based on a company’s financial health. Adherence to GAAP is crucial for maintaining trust and transparency in the financial markets.

GAAP is a common set of accounting rules, standards, and procedures issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States. These principles aim to provide a framework for creating financial statements that accurately reflect a company’s financial position. Internationally, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issues similar standards known as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). While there are differences between GAAP and IFRS, both share the fundamental goal of ensuring high-quality financial reporting.

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP)

GAAP encompasses a broad range of principles, but some key ones include the principle of historical cost, the matching principle, the revenue recognition principle, the full disclosure principle, and the going concern principle. The historical cost principle dictates that assets are recorded at their original purchase price. The matching principle requires that expenses be recognized in the same period as the revenues they generate. The revenue recognition principle Artikels when revenue should be recorded. The full disclosure principle mandates that all relevant information impacting a company’s financial position be disclosed. Finally, the going concern principle assumes that a business will continue to operate for the foreseeable future. These principles, along with others, work together to provide a comprehensive framework for financial reporting.

Importance of Following GAAP

Following GAAP is vital for several reasons. Firstly, it ensures consistency and comparability across different companies’ financial statements. Investors and creditors can readily compare the performance and financial position of various businesses because they are all using the same accounting rules. Secondly, it enhances the credibility and reliability of financial statements, fostering trust among stakeholders. This trust is fundamental for attracting investment and securing loans. Thirdly, adherence to GAAP minimizes the risk of misrepresentation and fraud. A standardized framework reduces opportunities for manipulation of financial data. Finally, compliance with GAAP is often a legal requirement for publicly traded companies, with significant penalties for non-compliance.

Impact of Violating GAAP, Accounting Basics: Everything You Need to Know

Violating GAAP can have serious consequences. Companies might face penalties and fines from regulatory bodies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Their reputation could suffer significantly, leading to a loss of investor confidence and difficulty in securing future financing. Furthermore, inaccurate financial reporting can mislead stakeholders, resulting in poor investment decisions and potential financial losses for investors and creditors. In extreme cases, violations of GAAP can lead to legal action and even criminal charges. For example, Enron’s accounting scandals, which involved significant violations of GAAP, resulted in the company’s collapse and severe consequences for its executives.

Examples of GAAP’s Impact on Financial Reporting

Consider a company that uses the LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) inventory costing method. Under GAAP, this method is acceptable, but it can impact the cost of goods sold and net income reported on the income statement, especially during periods of inflation. Conversely, using the FIFO (First-In, First-Out) method would result in different values. The choice of inventory costing method directly affects the reported financial figures, highlighting the significant influence of GAAP on financial reporting. Another example is the depreciation method chosen for fixed assets. Different depreciation methods (straight-line, double-declining balance, etc.) will produce different depreciation expenses and net income figures, all while remaining compliant with GAAP if properly applied. The consistency in applying a chosen method year after year is crucial, however, to avoid misleading investors.

Illustrative Example

Let’s solidify our understanding of accounting principles with a practical example. We’ll examine a common business transaction – purchasing inventory on credit – and trace its impact through the accounting system. This will illustrate the interconnectedness of the accounting equation, journal entries, and the overall accounting cycle.

This example demonstrates a simple business transaction, showcasing how it’s recorded and its effect on the fundamental accounting equation. Understanding this process is crucial for building a solid foundation in accounting.

Purchase of Inventory on Credit

Imagine a small bakery, “Sweet Success,” purchases flour on credit from a supplier, “Flour Power,” for $500. This means Sweet Success receives the flour but doesn’t pay immediately; they agree to pay Flour Power at a later date. This transaction affects several accounts within Sweet Success’s accounting system.

Journal Entry for the Transaction

The transaction is recorded using a journal entry, a standardized format for recording business transactions. A journal entry always involves at least one debit and one credit, ensuring the accounting equation remains balanced. The debit increases the balance of asset accounts (and expense accounts), while the credit increases the balance of liability and equity accounts (and revenue accounts).

The journal entry for Sweet Success’s flour purchase would look like this:

| Date | Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 26, 2024 | Inventory | $500 | |

| Accounts Payable | $500 |

The debit to Inventory increases the value of Sweet Success’s inventory (an asset). The credit to Accounts Payable increases Sweet Success’s liability to Flour Power. Notice that the total debits equal the total credits ($500 = $500), maintaining the balance of the accounting equation.

Impact on the Accounting Equation

The accounting equation,

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

, always remains balanced. Let’s see how this transaction affects it for Sweet Success:

Before the transaction, let’s assume Sweet Success had $1000 in assets and $500 in liabilities. Their equity would be $500 ($1000 – $500).

After the transaction:

* Assets increase by $500 (due to the increase in inventory). Total assets become $1500.

* Liabilities increase by $500 (due to the increase in Accounts Payable). Total liabilities become $1000.

* Equity remains unchanged at $500 ($1500 – $1000).

The equation remains balanced: $1500 (Assets) = $1000 (Liabilities) + $500 (Equity).

Step-by-Step Guide to Recording the Transaction

1. Identify the accounts affected: The transaction affects Inventory (an asset) and Accounts Payable (a liability).

2. Determine the debit and credit: Since Sweet Success is *receiving* inventory (increasing an asset), Inventory is debited. Since they are *incurring* a liability (owing money), Accounts Payable is credited.

3. Record the amounts: The amount of the debit and credit is equal to the value of the inventory purchased ($500).

4. Enter the date: The date of the transaction is recorded in the journal entry.

5. Post to the ledger: After recording the journal entry, the information is posted to the respective accounts in the general ledger. This provides a summary of all transactions affecting each account.

Common Accounting Software: Accounting Basics: Everything You Need To Know

Managing finances effectively is crucial for any business, regardless of size. Accounting software plays a vital role in streamlining financial processes, providing valuable insights, and ultimately contributing to business success. Choosing the right software can significantly impact efficiency and accuracy. This section explores various accounting software packages, comparing their features and benefits, and highlighting their importance for small businesses.

Types of Accounting Software

Several accounting software packages cater to different business needs and sizes. Popular options include cloud-based solutions like Xero and QuickBooks Online, and desktop-based applications such as QuickBooks Desktop and Sage 50cloud. Cloud-based software offers accessibility from anywhere with an internet connection, while desktop applications require installation on a computer. The choice depends on factors like budget, technical expertise, and business requirements. Larger businesses often opt for enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems that integrate accounting with other business functions.

Feature Comparison of Accounting Software Packages

A key differentiator among accounting software packages lies in their features. QuickBooks Online, for example, is known for its user-friendly interface and robust reporting capabilities, making it suitable for small businesses. Xero, another popular cloud-based option, excels in its integration with other business applications and its strong mobile app. QuickBooks Desktop, a desktop application, offers more advanced features and customization options compared to its online counterpart, often preferred by businesses with complex accounting needs. Sage 50cloud, another strong contender, provides a blend of cloud and desktop functionality. The selection depends on the specific features a business prioritizes, such as inventory management, payroll processing, and project accounting.

Benefits of Accounting Software for Small Businesses

Accounting software offers numerous advantages for small businesses. Automation of tasks like invoicing, expense tracking, and reconciliation saves significant time and reduces the risk of human error. Real-time financial data provides valuable insights into business performance, allowing for informed decision-making. Improved financial reporting facilitates easier tax preparation and compliance. Furthermore, many software packages offer features like bank reconciliation and inventory management, simplifying complex financial processes. The overall effect is increased efficiency, better financial control, and improved profitability.

Common Features Found in Accounting Software

Most accounting software packages share core features designed to manage the financial aspects of a business.

- Invoicing and Billing: Creating and sending invoices, tracking payments, and managing outstanding balances.

- Expense Tracking: Recording and categorizing expenses, often with features for receipt scanning and automated expense reports.

- Bank Reconciliation: Matching bank statements with accounting records to ensure accuracy.

- Financial Reporting: Generating various reports, including profit and loss statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements.

- Inventory Management: Tracking inventory levels, costs, and sales (particularly relevant for businesses selling goods).

- Payroll Processing: Calculating employee wages, deducting taxes, and generating paychecks (often requires additional modules or integrations).

- General Ledger: A central repository of all financial transactions.

Understanding Financial Ratios

Financial ratios are powerful tools used to analyze a company’s performance and financial health. They provide a standardized way to compare a company’s performance over time or against its competitors. By examining various ratios, stakeholders – including investors, creditors, and management – can gain valuable insights into a company’s profitability, liquidity, and solvency. Understanding these ratios is crucial for informed decision-making.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios assess a company’s ability to generate earnings from its operations. These ratios show how effectively a company is using its assets and managing its expenses to produce profits. Key profitability ratios include gross profit margin, net profit margin, and return on assets (ROA).

For example, a high gross profit margin indicates that a company is effectively managing its cost of goods sold, while a high net profit margin suggests strong overall profitability after all expenses are considered. A high ROA signifies efficient asset utilization in generating profits.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. These ratios are vital for assessing a company’s capacity to pay its bills as they come due. Important liquidity ratios include the current ratio and the quick ratio.

A current ratio above 1 generally indicates that a company has sufficient current assets to cover its current liabilities. The quick ratio, a more stringent measure, excludes inventory from current assets, providing a more conservative assessment of immediate liquidity.

Solvency Ratios

Solvency ratios gauge a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. These ratios are critical for evaluating a company’s financial stability and its capacity to survive over the long term. Key solvency ratios include the debt-to-equity ratio and the times interest earned ratio.

A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests that a company relies heavily on debt financing, potentially increasing financial risk. The times interest earned ratio indicates a company’s ability to cover its interest payments from its earnings. A higher ratio implies a greater capacity to meet interest obligations.

Examples of Ratio Calculation and Interpretation

Let’s consider a hypothetical company, “ABC Corp,” with the following data (in thousands):

- Total Assets: $10,000

- Total Liabilities: $6,000

- Total Equity: $4,000

- Net Sales: $15,000

- Net Income: $2,000

- Current Assets: $4,000

- Current Liabilities: $2,000

- Interest Expense: $500

We can calculate some key ratios:

- Net Profit Margin: (Net Income / Net Sales) * 100 = ($2,000 / $15,000) * 100 = 13.33%

- Current Ratio: Current Assets / Current Liabilities = $4,000 / $2,000 = 2.0

- Debt-to-Equity Ratio: Total Liabilities / Total Equity = $6,000 / $4,000 = 1.5

- Times Interest Earned: (Net Income + Interest Expense) / Interest Expense = ($2,000 + $500) / $500 = 5.0

Interpretation: ABC Corp has a healthy net profit margin, a strong current ratio indicating good short-term liquidity, a moderate debt-to-equity ratio suggesting a balance between debt and equity financing, and a high times interest earned ratio showing a substantial ability to cover interest payments.

Financial Ratios Used for Decision-Making

Financial ratios are integral to various decision-making processes. Investors use them to assess investment opportunities, evaluating profitability, risk, and growth potential. Creditors rely on ratios to evaluate a borrower’s creditworthiness, assessing the likelihood of loan repayment. Management uses ratios for internal performance monitoring, identifying areas for improvement and guiding strategic planning. Benchmarking against industry averages provides context and reveals relative strengths and weaknesses.

Table of Financial Ratios

| Ratio | Formula | Interpretation | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Profit Margin | (Revenue – Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue | Measures profitability after deducting cost of goods sold. | Profitability |

| Net Profit Margin | Net Income / Revenue | Measures overall profitability after all expenses. | Profitability |

| Return on Assets (ROA) | Net Income / Total Assets | Measures how efficiently assets generate profits. | Profitability |

| Current Ratio | Current Assets / Current Liabilities | Measures short-term liquidity. Higher is generally better. | Liquidity |

| Quick Ratio | (Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities | More conservative measure of short-term liquidity. | Liquidity |

| Debt-to-Equity Ratio | Total Liabilities / Total Equity | Measures the proportion of debt financing relative to equity. | Solvency |

| Times Interest Earned | EBIT / Interest Expense | Measures ability to cover interest payments. | Solvency |

Ultimate Conclusion

Mastering accounting basics opens doors to a deeper understanding of financial management. From interpreting balance sheets to understanding cash flow, this knowledge equips you to make sound financial decisions, whether for personal finances, a small business, or a larger organization. By understanding the core principles Artikeld here, you gain a powerful tool for navigating the financial world with confidence and clarity. This foundational knowledge provides a springboard for further exploration into more specialized accounting areas.

FAQ Section

What is the difference between financial and managerial accounting?

Financial accounting focuses on external reporting to stakeholders (investors, creditors), following GAAP. Managerial accounting focuses on internal reporting for management decision-making, not bound by GAAP.

How often should a business reconcile its bank statements?

Ideally, businesses should reconcile their bank statements monthly to identify discrepancies and prevent errors.

What are some common accounting software options for small businesses?

Popular options include QuickBooks, Xero, and FreshBooks, each offering varying features and pricing plans.

What is accrual accounting?

Accrual accounting recognizes revenue when earned and expenses when incurred, regardless of when cash changes hands, providing a more accurate picture of financial performance.