Understanding the Core Principles of Financial Accounting unveils the fundamental language of business. This journey explores the bedrock concepts—from the accounting equation and its components to the intricacies of financial statements—providing a clear path to comprehending how businesses track, analyze, and report their financial health. We’ll delve into the practical applications of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), examining the impact of various assumptions and methods on financial reporting. By the end, you’ll possess a solid understanding of how to interpret financial information and make informed decisions.

This exploration will equip you with the tools to navigate the world of financial reporting, allowing you to confidently analyze financial statements, understand the implications of accounting choices, and contribute meaningfully to financial discussions. Whether you’re a student, entrepreneur, or simply curious about the inner workings of business finance, this guide provides a clear and accessible introduction to the core principles that underpin all financial activity.

Fundamental Accounting Concepts

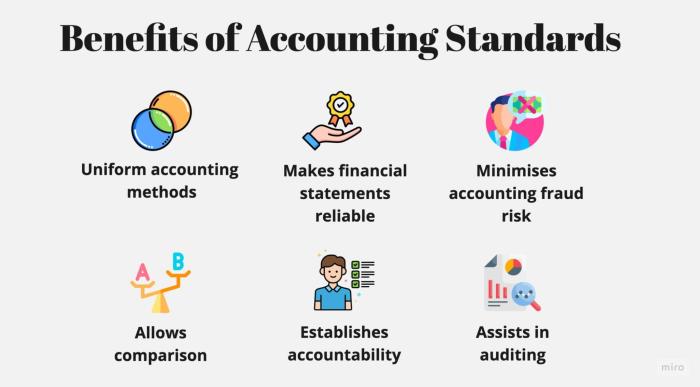

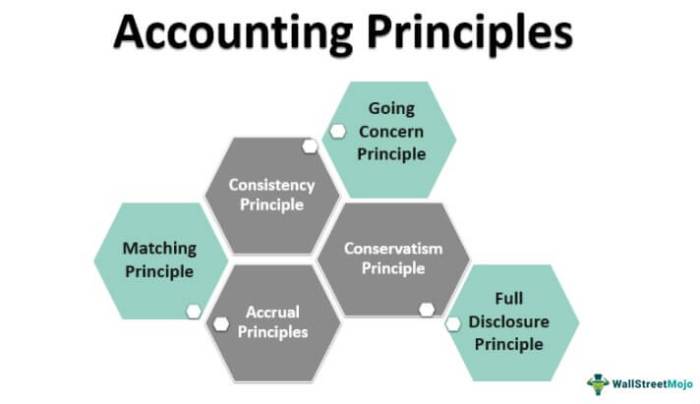

Financial accounting relies on a set of fundamental concepts and principles to ensure consistency and comparability across different companies’ financial statements. Understanding these principles is crucial for interpreting financial information accurately. This section will explore some key concepts, including generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), the cost principle, the going concern assumption, and a comparison of cash and accrual accounting.

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), Understanding the Core Principles of Financial Accounting

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are a common set of accounting rules, standards, and procedures issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States. These principles aim to ensure that financial statements are presented fairly and consistently, allowing for meaningful comparisons between companies. GAAP encompasses various concepts, including the cost principle, the going concern assumption, and the revenue recognition principle, among others. Adherence to GAAP is essential for publicly traded companies and many privately held companies as well. Deviations from GAAP must be clearly disclosed.

The Cost Principle

The cost principle dictates that assets should be recorded at their historical cost – the amount paid to acquire them at the time of purchase. This applies to all assets, including property, plant, and equipment (PP&E), inventory, and investments. For example, if a company buys a building for $1 million, it will be recorded on the balance sheet at $1 million, even if its market value later increases. This principle provides objectivity and avoids subjective valuations. However, depreciation, which systematically allocates the cost of an asset over its useful life, is an exception to this principle, as it gradually reduces the asset’s book value. For instance, if a company purchased a machine for $100,000 with a useful life of 10 years, it would record depreciation expense of $10,000 annually, reducing the asset’s book value over time.

The Going Concern Assumption

The going concern assumption presumes that a business will continue operating for the foreseeable future. This assumption is fundamental to many accounting practices, particularly in the valuation of assets and liabilities. For example, if a company is considered a going concern, it can record long-term assets at their historical cost and amortize them over their useful life. If, however, a company is deemed likely to go bankrupt, its assets might need to be valued at their liquidation value, significantly impacting its reported financial position. The going concern assumption influences the presentation of long-term assets and liabilities on the balance sheet. A company facing significant financial distress would be required to disclose this information, and potentially adjust its financial reporting to reflect the increased uncertainty.

Cash Basis versus Accrual Basis Accounting

Cash basis accounting recognizes revenue when cash is received and expenses when cash is paid. Accrual basis accounting, on the other hand, recognizes revenue when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, regardless of when cash changes hands. A small business might use cash basis accounting for its simplicity, while larger companies typically use accrual basis accounting, as it provides a more accurate reflection of a company’s financial performance over time. For example, a company selling goods on credit would record the revenue under accrual accounting when the sale is made, not when the payment is received. Conversely, if a company pays for insurance coverage in advance, the expense would be recorded over the period the insurance is in effect under accrual accounting, while the entire expense would be recorded in the year of payment under cash accounting.

Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

The accounting equation, Assets = Liabilities + Equity, forms the foundation of double-entry bookkeeping. Understanding the differences between these three fundamental account types is crucial.

| Account Type | Definition | Example | Normal Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | Resources owned by a company that provide future economic benefits. | Cash, Accounts Receivable, Inventory, Equipment | Debit |

| Liabilities | Obligations of a company to transfer economic resources to other entities. | Accounts Payable, Loans Payable, Salaries Payable | Credit |

| Equity | The residual interest in the assets of a company after deducting its liabilities; represents the owners’ stake in the business. | Common Stock, Retained Earnings | Credit |

The Accounting Equation and its Components

The accounting equation is the fundamental building block of double-entry bookkeeping. It represents the relationship between a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity, providing a snapshot of its financial position at any given time. Understanding this equation is crucial for interpreting financial statements and making informed business decisions.

The accounting equation states that a company’s assets are always equal to the sum of its liabilities and equity. This relationship is expressed as:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This equation reflects the fundamental principle that everything a company owns (assets) is financed either by what it owes to others (liabilities) or by the owners’ contributions (equity).

The Relationship Between Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

Assets are resources controlled by the company as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity. Examples include cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and equipment. Liabilities represent obligations of the company arising from past transactions or events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits. Examples include accounts payable, loans payable, and salaries payable. Equity represents the residual interest in the assets of the entity after deducting all its liabilities. It reflects the owners’ stake in the company.

Transaction Effects on the Accounting Equation

Every financial transaction affects at least two accounts, maintaining the balance of the accounting equation. For example, if a company purchases equipment with cash, the cash account (asset) decreases, and the equipment account (asset) increases. The total assets remain unchanged, and the equation remains balanced. Similarly, borrowing money increases both assets (cash) and liabilities (loans payable), maintaining the equation’s balance.

Journal Entries Illustrating Changes in Assets, Liabilities, and Equity

Let’s illustrate with some examples.

- Increase in Asset (Cash): A company receives $10,000 cash from a customer for services rendered.

Account Debit Credit Cash $10,000 Service Revenue $10,000 This increases both assets (cash) and equity (revenue increases retained earnings, a component of equity).

- Decrease in Asset (Cash): The company pays $5,000 rent.

Account Debit Credit Rent Expense $5,000 Cash $5,000 This decreases assets (cash) and decreases equity (expenses reduce retained earnings).

- Increase in Liability (Accounts Payable): The company purchases $2,000 of supplies on credit.

Account Debit Credit Supplies $2,000 Accounts Payable $2,000 This increases assets (supplies) and liabilities (accounts payable).

- Decrease in Liability (Accounts Payable): The company pays $1,000 on its accounts payable.

Account Debit Credit Accounts Payable $1,000 Cash $1,000 This decreases both assets (cash) and liabilities (accounts payable).

Impact of Owner’s Investments and Withdrawals

Owner investments increase both assets (usually cash) and equity. Owner withdrawals decrease assets (usually cash) and decrease equity. For instance, if the owner invests $20,000, cash increases and equity (owner’s capital) increases by the same amount. Conversely, if the owner withdraws $1,000, cash decreases and equity decreases.

Balancing the Accounting Equation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Balancing the accounting equation involves ensuring that the total assets always equal the sum of total liabilities and equity after each transaction. This is achieved through the double-entry bookkeeping system, where every transaction affects at least two accounts. The process involves:

- Identifying the accounts affected by the transaction.

- Determining the increase or decrease in each account.

- Recording the transaction using debits and credits, ensuring that debits equal credits.

- Calculating the new balances for all affected accounts.

- Verifying that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) remains balanced.

Financial Statements

Financial statements are the cornerstone of communicating a company’s financial performance and position to stakeholders. They provide a structured summary of financial data, allowing for analysis and informed decision-making. The three primary financial statements – the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement – work together to paint a comprehensive picture of a company’s financial health.

Income Statement

The income statement, also known as the profit and loss (P&L) statement, reports a company’s financial performance over a specific period, such as a quarter or a year. It focuses on revenues, expenses, and the resulting net income or net loss. Understanding the income statement is crucial for assessing profitability and identifying areas for improvement.

Common accounts found on the income statement include revenues (sales, service revenue), cost of goods sold (COGS), operating expenses (rent, salaries, utilities), interest expense, taxes, and net income (or net loss). For example, a retail company’s income statement would show its total sales revenue, the cost of the goods it sold, and the resulting gross profit. Subtracting operating expenses, interest, and taxes would then reveal the company’s net income.

Balance Sheet

The balance sheet provides a snapshot of a company’s financial position at a specific point in time. It follows the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. This equation highlights the relationship between what a company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the owners’ stake in the company (equity). Analyzing the balance sheet helps understand a company’s liquidity, solvency, and financial structure.

Common accounts found on the balance sheet include assets (cash, accounts receivable, inventory, property, plant, and equipment), liabilities (accounts payable, loans payable), and equity (common stock, retained earnings). For instance, a balance sheet for a manufacturing company would list its factory buildings as assets, its bank loans as liabilities, and the owners’ investment as equity. The information from the income statement, specifically net income, directly impacts the balance sheet. Net income increases retained earnings, which is a component of equity.

Cash Flow Statement

The cash flow statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of a company over a specific period. Unlike the income statement, which uses accrual accounting, the cash flow statement focuses solely on cash transactions. It categorizes cash flows into three main activities: operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. This statement is vital for assessing a company’s liquidity and its ability to meet its short-term and long-term obligations.

Common accounts shown in a cash flow statement include cash from operating activities (cash received from customers, cash paid to suppliers), cash from investing activities (purchase or sale of property, plant, and equipment), and cash from financing activities (issuance of debt, repayment of debt, payment of dividends). A technology company’s cash flow statement might show significant cash inflows from operating activities due to software sales, outflows from investing activities related to research and development, and inflows from financing activities if they secured venture capital.

Relationship Between Financial Statements

The three financial statements are interconnected. The net income from the income statement flows into the balance sheet, increasing retained earnings. The cash flow statement shows how cash transactions impact the cash balance reported on the balance sheet. Analyzing these statements together provides a more complete understanding of a company’s financial health.

| Statement | Key Components | Purpose | Interrelationships |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income Statement | Revenues, Expenses, Net Income | Shows profitability over a period. | Net income flows to the balance sheet (retained earnings). |

| Balance Sheet | Assets, Liabilities, Equity | Shows financial position at a point in time. | Reflects the impact of net income (from the income statement) and cash flows (from the cash flow statement). |

| Cash Flow Statement | Operating, Investing, Financing Activities | Shows cash inflows and outflows. | Changes in cash balance affect the balance sheet; cash flows impact the ability to generate net income. |

Debits and Credits

Understanding debits and credits is fundamental to double-entry bookkeeping, the system used to record financial transactions. This system ensures that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) always remains balanced. Every transaction affects at least two accounts, with one receiving a debit and the other a credit.

Debits and credits are simply entries that increase or decrease account balances. The effect depends on the type of account.

Rules of Debit and Credit

The basic rules governing debits and credits are crucial for accurate bookkeeping. Assets increase with debits and decrease with credits. Liabilities and equity increase with credits and decrease with debits. This seemingly simple system underpins the entire process of financial accounting.

| Account Type | Debit Effect | Credit Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Assets | Increase | Decrease |

| Liabilities | Decrease | Increase |

| Equity | Decrease | Increase |

Examples of Debit and Credit Entries

Let’s illustrate with some common transactions. Suppose a company purchases equipment for $10,000 cash. This transaction affects two accounts: Equipment (an asset) and Cash (an asset). The Equipment account increases (debit) by $10,000, while the Cash account decreases (credit) by $10,000.

Another example involves receiving payment from a customer for services rendered. This increases Cash (debit) and decreases Accounts Receivable (credit). If the company borrows $5,000 from a bank, Cash increases (debit) and Loans Payable (a liability) increases (credit).

Preparing a Trial Balance

A trial balance is a summary of all debit and credit balances in the general ledger. It’s used to verify that the total debits equal the total credits, confirming that the accounting equation remains balanced. To prepare a trial balance, list all accounts with their debit or credit balances. Then, sum the debit and credit columns. If the totals are equal, the trial balance is balanced. An unbalanced trial balance indicates an error that needs to be identified and corrected.

Comparison of Debit and Credit Balances

Different account types typically have either a debit or credit balance. Assets usually have debit balances, while liabilities and equity typically have credit balances. Revenue accounts normally have credit balances, and expense accounts usually have debit balances. However, it’s important to remember that these are typical balances and exceptions can occur.

Flowchart for Recording Transactions

The flowchart below visually represents the steps involved in recording a transaction using debits and credits.

[Imagine a flowchart here. The flowchart would begin with “Identify the accounts affected.” This would lead to two branches: “Debit account(s)” and “Credit account(s)”. Each branch would then lead to “Record the debit/credit entry in the journal” and finally converge at “Post the entry to the general ledger”.]

Analyzing Financial Statements

Understanding financial statements is crucial, but simply reading them isn’t enough. Analyzing them using key ratios and metrics provides valuable insights into a company’s financial health and performance. This allows for a deeper understanding beyond the raw numbers presented in the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement.

Common-Size Financial Statements

Common-size financial statements express each line item as a percentage of a base figure. For the balance sheet, this base is typically total assets, while for the income statement, it’s usually net sales or revenue. This standardization allows for easy comparison of companies of different sizes, or the same company across different periods. For example, comparing a company’s cost of goods sold as a percentage of sales over several years reveals trends in efficiency and pricing strategies. A consistent increase in this percentage might indicate rising input costs or declining pricing power. Conversely, a decrease could suggest improvements in operational efficiency or successful cost-cutting measures.

Key Financial Ratios and Their Interpretations

Financial ratios are calculated by dividing one financial statement item by another, providing insights into various aspects of a company’s performance. These ratios are broadly categorized into liquidity, profitability, and solvency ratios.

- Liquidity Ratios: Measure a company’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Examples include the current ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) and the quick ratio ((Current Assets – Inventory) / Current Liabilities). A high current ratio suggests strong liquidity, while a low ratio might indicate potential difficulties in meeting short-term debts. For instance, a current ratio of 2.0 indicates that a company has twice the amount of current assets to cover its current liabilities, suggesting a comfortable liquidity position.

- Profitability Ratios: Assess a company’s ability to generate profits. Examples include gross profit margin (Gross Profit / Net Sales), net profit margin (Net Profit / Net Sales), and return on equity (Net Profit / Shareholders’ Equity). A high net profit margin suggests efficient cost management and strong pricing power. A company with a consistently high return on equity is effectively utilizing its shareholders’ investments to generate profits.

- Solvency Ratios: Evaluate a company’s ability to meet its long-term obligations. Examples include the debt-to-equity ratio (Total Debt / Shareholders’ Equity) and the times interest earned ratio (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) / Interest Expense). A high debt-to-equity ratio suggests a higher reliance on debt financing, potentially increasing financial risk. A low times interest earned ratio indicates difficulty in covering interest payments, posing a solvency risk.

Limitations of Using Financial Ratios Alone

While financial ratios offer valuable insights, relying solely on them can be misleading. Ratios are only as good as the underlying financial data, and manipulation of accounting practices can distort the picture. Furthermore, ratios should be interpreted within the context of the industry and the company’s specific circumstances. A ratio that appears unfavorable in isolation might be perfectly acceptable given the industry norms or the company’s unique business model. A thorough analysis requires a holistic approach, combining ratio analysis with qualitative factors like management quality, competitive landscape, and economic conditions.

Usefulness of Financial Ratios for Different Stakeholders

Different stakeholders have varying interests and therefore find different ratios more useful.

- Investors: Focus on profitability and growth ratios, such as return on equity, earnings per share, and revenue growth rates, to assess the potential for future returns.

- Creditors: Primarily interested in liquidity and solvency ratios, such as the current ratio, debt-to-equity ratio, and times interest earned ratio, to assess the company’s ability to repay its debts.

Categorization of Financial Ratios

The following list categorizes financial ratios by the type of financial information they provide:

- Profitability Ratios: Gross profit margin, net profit margin, return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), operating profit margin.

- Liquidity Ratios: Current ratio, quick ratio, cash ratio, working capital turnover.

- Solvency Ratios: Debt-to-equity ratio, times interest earned ratio, debt-to-asset ratio.

- Efficiency Ratios: Inventory turnover, accounts receivable turnover, asset turnover.

- Market Value Ratios: Price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), price-to-book ratio (P/B), dividend yield.

Adjusting Entries and the Accrual Basis of Accounting

Accrual accounting, unlike cash accounting, recognizes revenue when earned and expenses when incurred, regardless of when cash changes hands. This leads to a more accurate reflection of a company’s financial performance and position. Adjusting entries are crucial for ensuring that the accrual basis is correctly applied at the end of an accounting period. They bridge the gap between the cash transactions recorded during the period and the economic events that have occurred but haven’t yet been reflected in the accounts.

Adjusting entries are made at the end of an accounting period to update accounts and ensure that the financial statements accurately reflect the company’s financial position and performance according to the accrual basis of accounting. These entries adjust the balances of accounts to ensure that revenues are recognized when earned and expenses are recognized when incurred, not just when cash is received or paid. Failing to make these adjustments would result in misleading financial statements.

Prepaid Expenses

Prepaid expenses represent assets that have been paid for in advance but have not yet been used or consumed. Examples include prepaid insurance, prepaid rent, and supplies. At the end of the accounting period, a portion of the prepaid expense has been used, requiring an adjusting entry to reduce the prepaid expense account and recognize the expense incurred. For instance, if a company paid $12,000 for a one-year insurance policy on January 1st, and it is December 31st, an adjusting entry would be needed to recognize the insurance expense for the year. The expense would be $10,000 ($12,000/12 months * 11 months). The adjusting entry would debit Insurance Expense for $10,000 and credit Prepaid Insurance for $10,000.

Accrued Revenues

Accrued revenues represent revenue that has been earned but not yet received in cash. Examples include interest receivable, accounts receivable, and service revenue earned but not yet billed. An adjusting entry is needed to recognize the revenue earned and the corresponding receivable. For example, if a company provides services worth $5,000 during December but does not bill the client until January, an adjusting entry would be needed on December 31st. The adjusting entry would debit Accounts Receivable for $5,000 and credit Service Revenue for $5,000.

Accrued Expenses

Accrued expenses represent expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid in cash. Examples include salaries payable, interest payable, and utilities payable. An adjusting entry is necessary to recognize the expense and the corresponding liability. For example, if employees worked during the last week of December but will be paid in January, an adjusting entry would be needed to recognize the salary expense. If the accrued salaries are $2,000, the adjusting entry would debit Salaries Expense for $2,000 and credit Salaries Payable for $2,000.

Depreciation Expense

Depreciation is the systematic allocation of the cost of a tangible asset over its useful life. Assets like buildings, equipment, and vehicles lose value over time due to wear and tear or obsolescence. An adjusting entry is required at the end of each accounting period to recognize depreciation expense and accumulate depreciation. For example, if a company has a piece of equipment with a cost of $100,000 and an estimated useful life of 10 years, the annual depreciation expense would be $10,000 ($100,000/10 years). The adjusting entry would debit Depreciation Expense for $10,000 and credit Accumulated Depreciation for $10,000.

Impact of Adjusting Entries on Financial Statements

Adjusting entries significantly impact the accuracy of the financial statements (Balance Sheet and Income Statement). Before adjusting entries, the financial statements may not reflect the true financial position and performance of the business. After adjusting entries, the financial statements provide a more complete and accurate picture. For instance, accrued revenues increase both assets (accounts receivable) and revenues on the income statement, while accrued expenses increase both liabilities (accounts payable) and expenses on the income statement.

Illustrative Journal Entries

The following journal entries illustrate common adjusting entries:

| Date | Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dec 31 | Insurance Expense | $10,000 | |

| Prepaid Insurance | $10,000 | ||

| To record insurance expense for the year | |||

| Dec 31 | Accounts Receivable | $5,000 | |

| Service Revenue | $5,000 | ||

| To record accrued service revenue | |||

| Dec 31 | Salaries Expense | $2,000 | |

| Salaries Payable | $2,000 | ||

| To record accrued salaries | |||

| Dec 31 | Depreciation Expense | $10,000 | |

| Accumulated Depreciation | $10,000 | ||

| To record depreciation expense |

The Closing Process

The closing process is a crucial step in the accounting cycle, marking the end of an accounting period and preparing the books for the next. It involves transferring the balances of temporary accounts (revenue, expense, and dividend accounts) to retained earnings, effectively resetting these accounts to zero for the new period. This ensures that the financial statements accurately reflect the results of operations for the period just concluded. Understanding this process is essential for accurately interpreting financial statements and ensuring the integrity of the accounting records.

Purpose of the Closing Process

The primary purpose of the closing process is to prepare the general ledger for the next accounting period. Temporary accounts, which track activity specific to a single accounting period, are closed to zero. This ensures that the financial statements reflect only the activities of the current period, preventing the accumulation of irrelevant data from previous periods. The closing process also updates the retained earnings account, which is a permanent account reflecting the cumulative profits and losses of the company.

Closing Temporary Accounts: A Step-by-Step Guide

The closing process involves several steps, all designed to systematically transfer the balances of temporary accounts to retained earnings. The order of these steps is important to ensure accuracy.

- Close Revenue Accounts: Debit each revenue account for its balance and credit the Income Summary account for the total of all revenue accounts. This transfers the revenue earned during the period to the Income Summary account.

- Close Expense Accounts: Credit each expense account for its balance and debit the Income Summary account for the total of all expense accounts. This transfers the expenses incurred during the period to the Income Summary account.

- Close Income Summary Account: Determine the net income or net loss by comparing the debit and credit balances in the Income Summary account. If the debit balance is greater (net loss), debit Retained Earnings and credit Income Summary. If the credit balance is greater (net income), credit Retained Earnings and debit Income Summary. This transfers the net income or net loss to Retained Earnings.

- Close Dividends Account: Debit Retained Earnings and credit the Dividends account for the amount of dividends declared during the period. This reduces Retained Earnings to reflect the distribution of profits to shareholders.

Impact of the Closing Process on the Balance Sheet

The closing process directly impacts the balance sheet by updating the retained earnings account. The retained earnings balance reflects the cumulative net income or net loss of the company, less any dividends paid. All other balance sheet accounts (assets, liabilities, and equity accounts other than retained earnings) remain unchanged by the closing process. This ensures the balance sheet continues to reflect the company’s financial position at the end of the period.

Balance Sheet Before and After Closing Entries

Let’s illustrate with a simplified example. Assume a company has the following balance sheet before closing:

| Assets | Liabilities & Equity |

|---|---|

| Cash: $10,000 | Accounts Payable: $2,000 |

| Accounts Receivable: $5,000 | Common Stock: $8,000 |

| Total Assets: $15,000 | Retained Earnings: $5,000 |

| Total Liabilities & Equity: $15,000 |

After closing entries reflecting a net income of $2,000 and dividends of $500, the balance sheet would show:

| Assets | Liabilities & Equity |

|---|---|

| Cash: $10,000 | Accounts Payable: $2,000 |

| Accounts Receivable: $5,000 | Common Stock: $8,000 |

| Total Assets: $15,000 | Retained Earnings: $6,500 |

| Total Liabilities & Equity: $15,000 |

Note that only the retained earnings balance has changed.

Preparation of Post-Closing Trial Balance

After the closing entries are posted, a post-closing trial balance is prepared. This trial balance lists only the permanent accounts (assets, liabilities, and equity accounts). The balances of the temporary accounts should all be zero. The post-closing trial balance serves as a verification that the closing process was completed accurately and that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) remains in balance. A post-closing trial balance showing only zero balances for temporary accounts confirms a successful closing process.

Final Review: Understanding The Core Principles Of Financial Accounting

Mastering the core principles of financial accounting is not merely about understanding debits and credits; it’s about gaining a powerful lens through which to view the financial health and performance of any organization. By understanding the interplay between assets, liabilities, equity, and the various financial statements, you gain a critical advantage in making informed decisions, whether in personal finance, business ventures, or investment strategies. The framework presented here offers a solid foundation for further exploration and deeper dives into specific areas of accounting and finance.

FAQ Insights

What is the difference between a debit and a credit?

Debits increase asset, expense, and dividend accounts, while decreasing liability, equity, and revenue accounts. Credits do the opposite.

What is the purpose of a trial balance?

A trial balance verifies the equality of debits and credits in the general ledger, ensuring the accounting equation remains balanced before preparing financial statements.

How are adjusting entries used?

Adjusting entries update accounts at the end of an accounting period to reflect transactions that haven’t been fully recorded, ensuring accurate financial reporting under accrual accounting.

What are some common financial ratios and their uses?

Examples include liquidity ratios (e.g., current ratio), profitability ratios (e.g., gross profit margin), and solvency ratios (e.g., debt-to-equity ratio). These ratios help assess different aspects of a company’s financial health.

Check what professionals state about Managerial Accounting Explained and its benefits for the industry.