Accounting for Inventory FIFO vs LIFO Explained: Understanding how businesses account for inventory is crucial for accurate financial reporting. This exploration delves into two primary methods: First-In, First-Out (FIFO) and Last-In, First-Out (LIFO). We’ll examine their core mechanics, compare their impacts on financial statements, and consider the factors influencing the choice between them. This guide aims to provide a clear and comprehensive understanding of these essential inventory accounting techniques.

We will analyze how each method affects cost of goods sold, ending inventory, gross profit, net income, and tax liability. Furthermore, we’ll dissect the implications of choosing one method over the other, including the potential for manipulating earnings and the importance of maintaining consistency. Real-world examples will illustrate the practical application of FIFO and LIFO, highlighting the differences in outcomes under varying price conditions.

Introduction to Inventory Accounting Methods

Inventory accounting is a crucial aspect of financial reporting for businesses that hold goods for sale. Its primary purpose is to accurately track the movement and value of inventory throughout the accounting period, ensuring that the financial statements reflect a true and fair view of the company’s financial position. This involves recording purchases, sales, and any losses or damages to inventory. Accurate inventory accounting is essential for making informed business decisions, complying with accounting standards, and avoiding potential legal issues.

Accurate inventory valuation is paramount for several reasons. It directly impacts the cost of goods sold (COGS), which in turn affects gross profit, net income, and ultimately, the company’s tax liability. An inaccurate inventory valuation can lead to misstated financial statements, potentially misleading investors and creditors. Furthermore, accurate valuation helps businesses manage inventory levels effectively, minimizing storage costs and preventing stockouts or overstocking. Proper valuation also aids in pricing strategies and profitability analysis.

Several methods exist for costing inventory, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of method depends on various factors, including the nature of the business, the industry, and the specific requirements of accounting standards. Common inventory costing methods include First-In, First-Out (FIFO), Last-In, First-Out (LIFO), and Weighted-Average Cost. These methods differ in how they assign costs to the goods sold and the ending inventory.

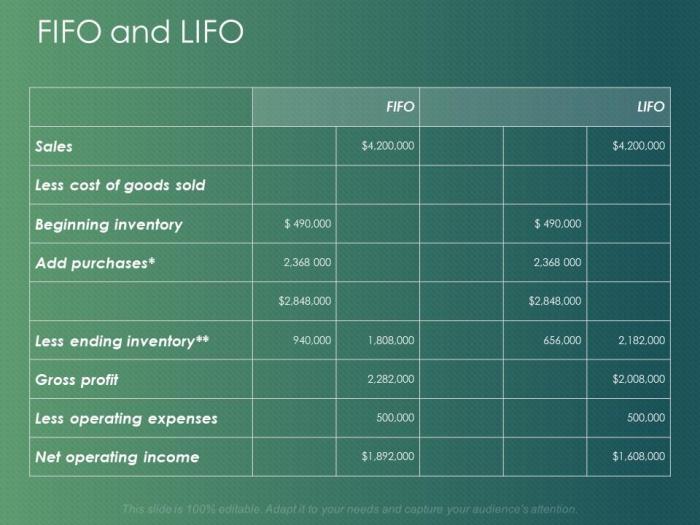

Comparison of FIFO and LIFO

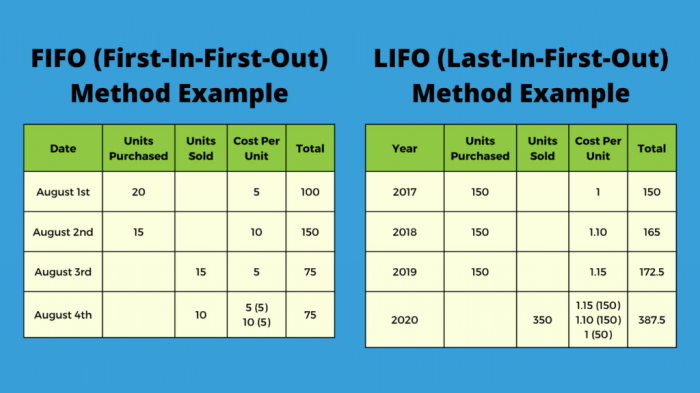

The following table compares the core differences between the FIFO and LIFO inventory costing methods:

| Feature | FIFO (First-In, First-Out) | LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost Flow Assumption | Assumes that the oldest inventory items are sold first. | Assumes that the newest inventory items are sold first. |

| Impact on COGS | COGS reflects the cost of the oldest inventory. | COGS reflects the cost of the newest inventory. |

| Impact on Ending Inventory | Ending inventory reflects the cost of the newest inventory. | Ending inventory reflects the cost of the oldest inventory. |

| Tax Implications (in inflationary environments) | Generally results in lower COGS and higher taxes. | Generally results in higher COGS and lower taxes. |

FIFO (First-In, First-Out) Method Explained

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method assumes that the oldest inventory items are sold first. This means the cost of goods sold (COGS) reflects the cost of the earliest acquired inventory, while the ending inventory reflects the cost of the most recently acquired inventory. This approach aligns with the natural flow of goods in many businesses, particularly those dealing with perishable goods.

FIFO Assumption Regarding Inventory Flow

FIFO operates on the principle that the first units purchased are the first units sold. This is a crucial assumption because it directly impacts how the cost of goods is assigned. Imagine a bakery; the oldest loaves of bread are likely the ones sold first, followed by progressively newer ones. This is a typical representation of FIFO in action. This method simplifies inventory tracking, especially in situations with minimal spoilage or obsolescence.

FIFO Calculation of Cost of Goods Sold and Ending Inventory

Let’s illustrate FIFO with an example. Suppose a company purchased three batches of inventory:

- Batch 1: 10 units at $10 each

- Batch 2: 15 units at $12 each

- Batch 3: 20 units at $15 each

The company sold 25 units during the period. Using FIFO, we assume the first 10 units sold came from Batch 1, and the remaining 15 units came from Batch 2.

Therefore:

Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) = (10 units * $10) + (15 units * $12) = $100 + $180 = $280

Ending Inventory = (5 units * $12) + (20 units * $15) = $60 + $300 = $360

FIFO’s Impact on Financial Statements During Inflation

During periods of inflation, when prices are rising, FIFO generally results in a lower COGS and a higher net income compared to LIFO. This is because the older, cheaper inventory is used to calculate COGS, leaving the more expensive, newer inventory in ending inventory. For example, consider a company selling widgets. If the price of widgets increases throughout the year, FIFO will report a lower COGS, leading to a higher profit margin. This higher profit, in turn, can lead to higher taxes.

Let’s consider a simplified scenario. A company purchased 100 widgets at $1 each in January and 100 widgets at $1.50 each in December. They sold 150 widgets during the year. Under FIFO, COGS would be calculated as (100 * $1) + (50 * $1.50) = $175. Ending inventory would be (50 * $1.50) = $75. If prices remained constant, COGS would have been $150. The difference highlights the impact of inflation on reported profit under FIFO.

FIFO’s Effect on Tax Liability

Because FIFO generally leads to higher reported net income during inflationary periods, it also results in a higher tax liability. The higher net income increases the taxable income, thus increasing the tax owed. This is a significant consideration for businesses, as choosing FIFO can have substantial financial implications. For instance, if a company’s tax rate is 25%, the difference in COGS between FIFO and LIFO (as shown in the previous example) would lead to a difference in tax liability of ($25 difference in COGS * 0.25) = $6.25. While seemingly small in this simplified example, this effect can be substantial for larger companies with significant inventory turnover.

LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) Method Explained

LIFO, or Last-In, First-Out, is an inventory accounting method that assumes the most recently acquired items are the first ones sold. This contrasts sharply with FIFO, where the oldest items are assumed to be sold first. The choice between LIFO and FIFO significantly impacts a company’s reported financial results, particularly during periods of inflation or deflation.

LIFO Inventory Flow Assumption

The core assumption of LIFO is that the last units purchased are the first units sold. Imagine a stack of pancakes; with LIFO, you eat the pancake on top (the last one added) first. This method directly reflects the physical flow of inventory in certain industries, such as those dealing with perishable goods or those with rapidly changing product lines. However, it’s important to note that the actual physical flow of inventory doesn’t always need to match the LIFO accounting method.

LIFO Cost of Goods Sold and Ending Inventory Calculation

Let’s revisit the FIFO example and apply LIFO. Suppose a company purchased inventory as follows:

| Date | Units Purchased | Cost per Unit |

|---|---|---|

| January 1 | 100 | $10 |

| March 1 | 50 | $12 |

| May 1 | 75 | $15 |

The company sold 150 units during the year. Using LIFO:

* Cost of Goods Sold: We first assume the 75 units purchased on May 1 were sold ($15/unit * 75 units = $1125). Then, we assume 75 of the 100 units purchased on January 1 were sold ($10/unit * 75 units = $750). The total cost of goods sold under LIFO is $1125 + $750 = $1875.

* Ending Inventory: We have 25 units remaining from the January 1 purchase ($10/unit * 25 units = $250) and 50 units remaining from the March 1 purchase ($12/unit * 50 units = $600). The total ending inventory under LIFO is $250 + $600 = $850.

LIFO’s Impact on Financial Statements During Inflation

During periods of inflation, when the price of goods increases over time, LIFO generally results in a higher cost of goods sold and a lower net income compared to FIFO. This is because the higher costs of the most recently purchased goods are assigned to the cost of goods sold, reducing the reported profit. For example, if a company uses LIFO during a period of significant inflation, its reported net income will be lower than if it used FIFO. This lower net income translates to lower taxes payable (as explained below) and a lower valuation of inventory on the balance sheet. Conversely, if prices are falling (deflation), LIFO would result in a lower cost of goods sold and higher net income.

LIFO’s Effect on Tax Liability, Accounting for Inventory FIFO vs LIFO Explained

Because LIFO results in a higher cost of goods sold during inflation, it leads to a lower reported net income. This lower net income, in turn, results in a lower taxable income and therefore a lower tax liability. This is a significant advantage for companies operating in inflationary environments, as it allows them to defer tax payments. However, it is important to note that the IRS has specific rules and regulations surrounding the use of LIFO, and companies must meet certain criteria to qualify. For example, the use of LIFO can lead to a timing difference between financial reporting and tax reporting, which can create complexities in financial statement analysis.

Comparing FIFO and LIFO

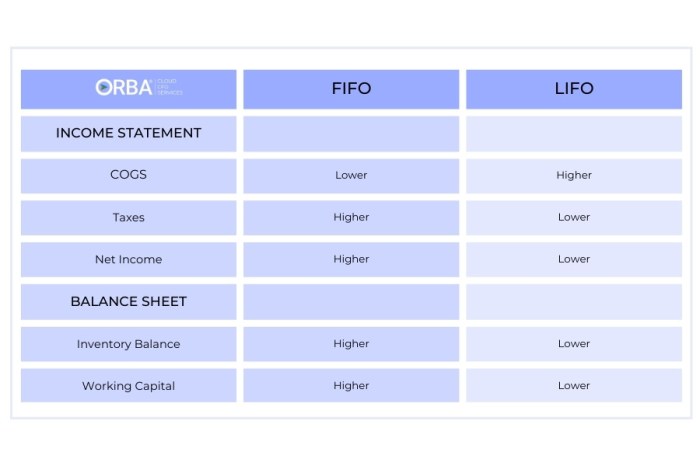

Choosing between FIFO (First-In, First-Out) and LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) inventory costing methods significantly impacts a company’s financial statements. The method selected affects the cost of goods sold, gross profit, net income, and the valuation of inventory on the balance sheet. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate financial reporting and analysis.

Impact on Gross Profit

FIFO and LIFO methods yield different gross profit figures, particularly during periods of fluctuating prices. Under FIFO, the cost of goods sold reflects the older, lower-cost inventory first, leaving higher-cost inventory on the balance sheet. This results in a higher gross profit during periods of rising prices. Conversely, LIFO assigns the cost of the most recently purchased (higher-cost) inventory to the cost of goods sold, leading to a lower gross profit in inflationary environments. In deflationary periods, the effects are reversed.

Impact on Net Income

The differences in gross profit directly translate to differences in net income. Higher gross profit under FIFO, all else being equal, leads to higher net income. Conversely, LIFO’s lower gross profit results in lower net income during inflationary periods. This difference in net income impacts various aspects of the business, including tax liabilities (as income tax is calculated on net income), investor perception, and creditworthiness. For example, a company using LIFO during a period of inflation will report lower net income and therefore pay less in taxes compared to a company using FIFO.

Impact on Inventory Valuation

The inventory valuation on the balance sheet also differs significantly between FIFO and LIFO. FIFO reports ending inventory at the most recent costs, reflecting the current market value more closely. LIFO, on the other hand, values ending inventory at the oldest costs. During inflation, FIFO will show a higher inventory value on the balance sheet than LIFO, potentially creating a more positive perception of the company’s asset base. Conversely, in deflation, LIFO would show a higher inventory value.

Impact on Key Financial Ratios

The choice between FIFO and LIFO influences several key financial ratios. The table below summarizes these differences, assuming a period of rising prices:

| Ratio | FIFO | LIFO | Impact of Rising Prices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue) | Higher | Lower | FIFO shows higher profitability |

| Net Profit Margin (Net Income / Revenue) | Higher | Lower | FIFO shows higher profitability |

| Inventory Turnover (Cost of Goods Sold / Average Inventory) | Potentially Higher (depends on inventory levels) | Potentially Lower (depends on inventory levels) | Difference depends on the specific inventory levels |

| Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) | Potentially Higher (due to higher inventory valuation) | Potentially Lower (due to lower inventory valuation) | Difference depends on the relative size of inventory compared to other current assets. |

Choosing Between FIFO and LIFO

Selecting between the First-In, First-Out (FIFO) and Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) inventory costing methods is a crucial decision for businesses, significantly impacting their financial statements and tax liabilities. The optimal choice depends on a careful consideration of several interacting factors.

Factors Influencing the Choice Between FIFO and LIFO

The decision of whether to use FIFO or LIFO hinges on several key factors. These factors are often interconnected and require a holistic assessment to determine the most appropriate method for a specific business context. For example, a business experiencing rapid inflation might find LIFO advantageous for tax purposes, but FIFO might provide a more accurate reflection of the current cost of goods sold. Conversely, a business in a stable price environment might find little practical difference between the two methods.

Industry Regulations and Inventory Method Selection

Industry regulations play a significant role in shaping the selection of an inventory method. Some industries might have specific accounting standards or guidelines that dictate or strongly influence the choice between FIFO and LIFO. For instance, certain regulatory bodies might favor FIFO due to its perceived greater consistency with the actual flow of goods. Compliance with these regulations is paramount to avoid penalties and maintain the integrity of financial reporting. Failing to comply with relevant regulations could result in financial penalties and reputational damage.

Tax Implications of Choosing an Inventory Method

The tax implications of choosing between FIFO and LIFO are substantial, especially during periods of inflation. During inflationary periods, LIFO generally results in a higher cost of goods sold, leading to lower taxable income and lower tax liability. This is because the most recently purchased (and most expensive) goods are assumed to be sold first. Conversely, FIFO, during inflation, leads to a lower cost of goods sold, resulting in higher taxable income and a higher tax liability. The impact on tax liability can be considerable, particularly for businesses with large inventories. A company with a large inventory of goods whose prices have increased significantly over time could save substantial tax money using LIFO.

Importance of Consistency in Applying the Chosen Method

Consistency in applying the chosen inventory method is critical for maintaining the reliability and comparability of financial statements over time. Once a method is selected, it should be consistently applied from period to period unless there is a justifiable reason for a change. Changes in inventory methods must be disclosed and explained in the financial statements to avoid misleading investors and other stakeholders. Inconsistent application can lead to difficulties in financial analysis and may raise concerns about the accuracy and reliability of the financial reporting. A change in method might require adjustments to previously reported financial statements to ensure consistency.

Illustrative Examples

Let’s solidify our understanding of FIFO and LIFO with concrete examples. We’ll follow a company’s inventory journey, showcasing how each method impacts the financial statements, particularly the cost of goods sold and ending inventory. The impact of fluctuating prices will also be highlighted.

FIFO Example: Acme Widgets

Acme Widgets, a small manufacturing company, produces widgets. During the month of July, they purchased widgets at the following costs and quantities:

| Date | Units Purchased | Cost per Unit | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 5 | 100 | $10 | $1000 |

| July 15 | 150 | $12 | $1800 |

| July 25 | 50 | $15 | $750 |

During July, Acme sold 200 widgets. Using FIFO, we assume the first units purchased are the first units sold. Therefore:

* 100 units sold at $10 each = $1000

* 100 units sold at $12 each = $1200

Total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) under FIFO: $1000 + $1200 = $2200

Ending Inventory under FIFO: (50 units x $15) = $750

LIFO Example: Acme Widgets (Same Data)

Now, let’s analyze Acme Widgets’ July inventory using LIFO. With LIFO, we assume the last units purchased are the first units sold.

* 50 units sold at $15 each = $750

* 150 units sold at $12 each = $1800

Total Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) under LIFO: $750 + $1800 = $2550

Ending Inventory under LIFO: (100 units x $10) = $1000

Comparison of FIFO and LIFO Results

| Method | Cost of Goods Sold | Ending Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| FIFO | $2200 | $750 |

| LIFO | $2550 | $1000 |

As demonstrated, the choice of inventory method significantly impacts both the cost of goods sold and the value of ending inventory. LIFO resulted in a higher COGS and a higher ending inventory value compared to FIFO in this scenario due to the rising prices of widgets throughout July.

Impact of Price Changes

The difference between FIFO and LIFO becomes more pronounced when prices fluctuate significantly. In periods of rising prices (like in our example), LIFO reports a higher cost of goods sold, resulting in lower net income and lower taxes. Conversely, FIFO reports a lower cost of goods sold, leading to higher net income and higher taxes. In periods of falling prices, the effects are reversed. This impact on net income and taxes is a crucial factor in choosing between FIFO and LIFO. The choice can strategically influence a company’s tax liability and reported profitability.

Limitations of FIFO and LIFO

While FIFO and LIFO offer valuable insights into inventory valuation and cost of goods sold, they are not without their limitations. Both methods can distort financial reporting, particularly during periods of significant inflation or deflation, leading to potential misinterpretations of a company’s financial health. Understanding these limitations is crucial for accurate financial analysis and decision-making.

FIFO’s Distortion of Financial Reporting

FIFO, by assuming that the oldest inventory is sold first, can overstate both ending inventory and net income during periods of inflation. This is because the cost of goods sold reflects older, lower costs, while the ending inventory reflects newer, higher costs. This can lead to a higher reported profit than would be the case under a different valuation method, potentially misleading investors and creditors who rely on these figures. Conversely, during periods of deflation, FIFO understates net income and overstates the cost of goods sold. This discrepancy can make accurate performance comparisons across periods difficult and potentially skew the perception of profitability. For example, a company experiencing inflation might show significantly higher profits under FIFO compared to a company using a different method, even if their actual sales volumes and margins are comparable. This difference can lead to an unfair comparison of performance.

LIFO’s Distortion of Financial Reporting

LIFO, conversely, can understate net income during inflationary periods because the cost of goods sold reflects the higher, more recent costs. This results in a lower reported profit and, consequently, lower tax liability. However, it also understates the value of ending inventory, which may not accurately reflect the current market value of the goods. During deflationary periods, LIFO overstates net income and understates the cost of goods sold, creating a similar distortion to FIFO but in the opposite direction. The mismatch between reported income and the actual economic reality can impact investment decisions and creditworthiness assessments. For instance, a company using LIFO might appear less profitable than it actually is during inflationary periods, potentially hindering its ability to secure loans or attract investors.

Situations Where Neither FIFO Nor LIFO is Appropriate

Neither FIFO nor LIFO is suitable in situations where inventory items are not easily identifiable or interchangeable. For example, custom-made products or perishable goods with short shelf lives may not lend themselves to the FIFO or LIFO assumptions. In such cases, other inventory valuation methods, such as the specific identification method, might be more appropriate. The specific identification method tracks the cost of each individual item, providing a more accurate reflection of the cost of goods sold and ending inventory but requiring more detailed record-keeping. Furthermore, if a company’s inventory is highly volatile, or experiences significant price fluctuations, both FIFO and LIFO might produce misleading results, necessitating the use of a more nuanced valuation approach.

Potential for Earnings Manipulation

The choice between FIFO and LIFO can be used to manipulate earnings, although this is ethically questionable and often subject to regulatory scrutiny. During periods of inflation, a company might choose LIFO to reduce its tax liability by reporting lower profits. Conversely, a company might opt for FIFO to inflate its reported profits, potentially boosting its stock price or attracting investors. This manipulation can create an inaccurate picture of the company’s financial performance and mislead stakeholders. While the choice of method is permitted under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), any attempt to artificially manipulate earnings through the selective application of these methods can have serious legal and reputational consequences. Companies should always strive for transparency and consistency in their accounting practices, ensuring that the chosen method accurately reflects the underlying economic reality of their business.

Outcome Summary

In conclusion, the selection between FIFO and LIFO inventory accounting methods significantly impacts a company’s financial statements and tax obligations. While FIFO offers a more intuitive approach reflecting actual inventory flow, LIFO can provide tax advantages during inflationary periods. The optimal method depends on various factors, including industry regulations, company-specific circumstances, and long-term financial goals. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each approach is vital for making informed decisions and ensuring accurate financial reporting.

FAQ Explained: Accounting For Inventory FIFO Vs LIFO Explained

What is the impact of using LIFO during deflationary periods?

During deflation, LIFO can result in a lower cost of goods sold and higher net income compared to FIFO, as the most recently purchased (and cheaper) items are assumed to be sold first.

Is LIFO allowed under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)?

No, LIFO is not permitted under IFRS. IFRS generally requires the use of FIFO or other methods that reflect the actual flow of inventory.

Can a company switch between FIFO and LIFO methods?

Generally, a change in inventory accounting methods requires disclosure and may need justification. Consistency is key, though changes are sometimes allowed under specific circumstances and with proper accounting treatment.

Obtain direct knowledge about the efficiency of Top 10 Accounting Apps for Business Owners through case studies.